As more of us become increasingly attuned to and educated about the benefits—indeed, the necessity—of a more environmentally friendly lifestyle, multifamily buildings and residential communities are turning toward new ‘green’ features to update and enhance their lobbies and other common spaces. Architects and designers regularly collaborate with boards and volunteer design committees to include features like green walls and indoor fountains in lobby renovation projects to give a feeling of organic tranquility to shared spaces.

Biophilia

“Biophilia,” explains Sarah Marsh, principal of MAAI Marsh Architects in New York City, “is the concept that human beings have an innate desire to connect with nature, both indoors and outdoors. Specifically, we seek daylight and have a sensorial connection with natural materials, colors, shapes, and forms found in nature.”

The benefits of this connection are many, Marsh says. “Time with nature combats depression, anxiety, and mood disorders, improves sleep, improves happiness, boosts attention and creativity, and increases social interaction. Because biophilia offers solutions potentially capable of improving mental, physical, and emotional states, it’s likely that it’s more than just an architectural fad.”

While the concept of biophilia has gotten more press in the last couple of years (particularly as the pandemic brought into sharp focus just how important fresh air and sunlight are to physical and mental health), “it is not a subject which should be considered ‘new’ or ‘alternative,’” says Marsh, who notes that the concept really began gaining traction in architectural and design circles back in the 1990s.

Biophilic design is a broad concept that can include almost anything that brings aspects of nature into a space. That could—and often does—include elements like green walls, fountains, potted plants, and even koi ponds. The question for condo and co-op communities interested in incorporating biophilic elements into their own common areas is twofold: What will that space accommodate, and at what cost to install and maintain in terms of both dollars and manpower?

Green Walls & Water Features

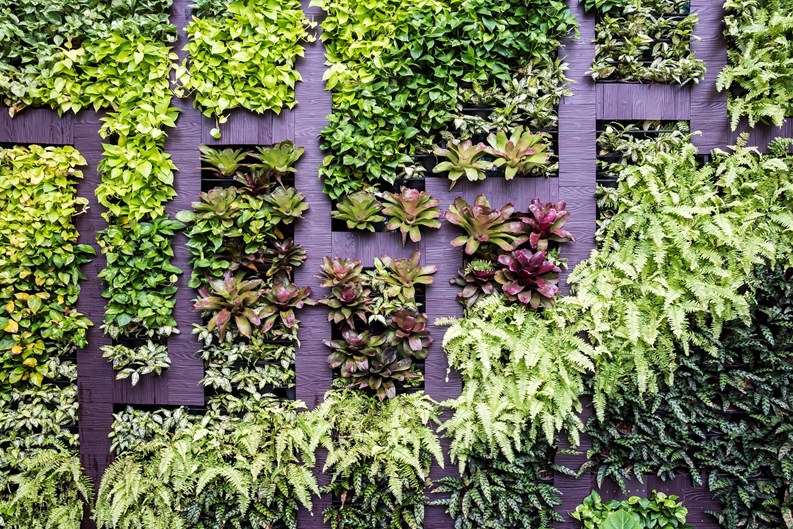

A green wall is a vertical wall surface (indoors or out) with living or preserved plants growing out of or suspended from it—and they are not a new concept. Green walls have been around at least since the 1990s, and have been steadily gaining popularity ever since. “We just used a green wall in a lobby,” says Marilyn Sygrove, principal of Sygrove Associates Design Group in Manhattan. “It’s a terrific product, very impactful, with absolutely no maintenance, because it is actually preserved moss. We love it—and if it’s in the right location, a green wall can be tastefully used in both newer and traditional spaces.”

And they’re more than just pretty to look at, says Trevor Smith of Land Escapes Design in Belmont, Massachusetts. In addition to helping freshen the air, living green walls “also absorb harmful VOCs [volatile organic compounds], like formaldehyde and benzene that are given off by rugs, paints, furniture, and appliances. All these plastics and all these man-made items around us are constantly off-gassing and releasing subtle chemicals into the air, and plants absorb those chemicals and detoxify the air around us.”

Both older and new buildings can benefit from green walls, says Marsh, and “they are available in a large range of types and sizes.”

Along with green walls, water features like fountains and koi ponds have long been a feature in apartment building lobbies. This author recalls visiting his grandparents in a mid-century apartment building in Forest Hills, Queens, which had a koi pond. It was a very cool and different thing to have in a lobby, which can be a big plus when it comes to aesthetics and curb appeal—but the pros note that any project requiring water, whether as a lifeline for live plants or as a feature unto itself, also requires a lot of maintenance and upkeep. Some buildings, particularly older ones, may need some significant retrofitting in order to support an ambitious indoor landscape.

“To start, walls must support a minimum of 18 pounds per square foot,” says Marsh, though load bearing capacity is variable, depending on the construction, irrigation hardware, and plant material being used.

According to Smith, any wall with studs should work as far as mounting a living garden. “There are multiple systems,” he explains, “but usually a living wall averages about between, say, 25 and 65 pounds per square foot when totally saturated. I always tell people, ‘I need a wall that can hold 65-plus pounds per square foot when saturated.’”

For living walls, “Space is also needed for an irrigation control unit (ICU), a metal security cabinet, power, water supply, drain, fertilizer, and a supply tank, among other supporting components,” Marsh adds. “Lighting of the green wall panel or panels can be provided by fixtures at the ceiling or locally with small LED fixtures.”

Most older buildings should be capable of accommodating green walls, water features, and other biophilic elements, Marsh continues. There are caveats, though. “Older buildings can present issues that require special installation solutions. If the walls are solid masonry, that can cause issues when it comes to concealing water supply and drain piping and electric wiring conduits. There may be buildings where existing conditions necessitate a change to the desired design or lead to abandoning part or all of the design.” And while that’s not common, Marsh notes that “plumbing drains can be difficult in some properties. Electric panels or the available power may also be difficult problems to resolve. An older building’s structural framing can cause headaches that have to be worked around.”

“The great thing about a living wall is, it’s just beautiful to look at,” says Smith. “It’s wonderful...like a rotating piece of artwork, which is great for say a common area. But they also are wonderful in urban environments because they don’t take up any floor space—or they take up very little. You can have 50 plants on the wall, but if you were to have 50 [floor] plants in your house, it would look like Wild Kingdom. With a green wall, you get all the benefits of plants without taking up a whole lot of floor space—and you get the added benefit of living artwork.”

Xeriscaping

Xeriscaping is a form of low-maintenance landscaping that requires little to no watering. One could say that it represents the intersection of biophilic and environmentally friendly design.

With several parts of the country experiencing historic drought conditions, reducing the consumption of water is a prime goal of xeriscaping projects, says Marsh. Less water consumption also brings down electrical costs associated with green walls to treat and deliver water.

“Drought-tolerant or native plants are intended to reduce water consumption,” explains Marsh. That means that the look of biophilic installations will be different in different regions—which is part of the aesthetic charm, as well as the eco-friendliness of the approach. Using attractive stones, pavers, and other hard elements along with plant species native to the area that can thrive with minimal maintenance is what makes xeriscaping a very popular alternative to ‘thirsty’ plants and grasses that require enormous amounts of water and care just to stay alive.

Interior xeriscaping is also an option, though Marsh notes that unless the plant elements in such a design are entirely artificial, indoor installations will likely still need some supplemental irrigation and the infrastructure to deliver it.

Any Takers?

According to Sygrove, residential developers often include water features in the lobbies of their new buildings for the dynamic yet serene, nurturing life force such elements bring to the space. Developers are one thing; boards often think differently.

“I have presented water walls [to boards] over the years, and have had no takers,” Sygrove says, “because though there is minimal water and it constantly circulates, boards have concerns about it leaking, and about potential smells. Boards are also concerned that residents and visitors will throw things—like pennies, for example—into it as if it were the Trevi Fountain, so to date I haven’t been able to incorporate any into our designs. I would love to, however—and I won’t give up on offering the option!” (The author recalls tossing more than one penny into the koi pond at his grandparents’ building, so those hesitant boards may be on to something.)

Penny-tossing worries notwithstanding, “water features are a natural biophilic element,” says Marsh. “They can and do contribute to a relaxing ambiance, whether from a still, shallow pool or by mimicking moving water sounds in nature. There’s almost no limit to water feature designs for the floor, wall, and even the ceiling. Beginning with floor-mounted water features, there are floating fountains, floor fountains, and bubbling fountains. I’ve even seen a water feature with a glass floor that was part of a shallow second-floor pool, with water falling down to create a wall or ceiling feature on the first floor below.”

Marsh goes on to say that water walls can incorporate everything from glass to acrylic, tile, stone, and other natural materials into their design—and low-voltage LED lighting can be added to accentuate the cascading water with soothing effects and spectacular visual sensory input.

Water walls and falls are also scalable to a given space. Marsh has seen designs exceeding 100 feet long and 30 feet tall, and says they can be flat, curved, or serpentine. What’s possible is limited only by imagination, budget, and what the given infrastructure will accommodate.

“Waterfalls can be just about any design the client is willing to pay for,” says Marsh. “The range can be as simple as a spout [or as complex as] a multi-story extravaganza. There are also step waterfalls terminating in a pool. The simple spout can be a metal fabrication or handmade glazed terra cotta or hand-hewn stone.”

A Splash from the Past

Fountains have long been a popular architectural element, both indoors and out. The Apthorp in Manhattan, one of the most famous historic apartment communities in the world, has featured a fountain since it was built in 1911. It sits in the building’s interior garden, and has been beloved by residents for more than a century.

Peter Mettham is a management representative at The Apthorp, which is managed by Gumley Haft, a management firm based in Manhattan. He says the building’s fountain is easy to maintain, precisely because of its age and relatively low tech. “Prior to winter, the fountain is drained and the statues are covered with tarps,” he says. “In the spring, the basin is scrubbed and filled with water, and the fountain can be turned back on. There’s some elbow grease involved in cleaning and scrubbing, but it’s a low-maintenance item. Filters are used to keep the system running properly. We replace these filters quarterly. In summer, we do have to top off the water in the system due to evaporation, but beyond that and the quarterly filter replacement, nothing specific needs to be done. As an annual maintenance item, there is about 16 hours of total labor involved in fountain maintenance.”

The annual cost of upkeep and maintenance—including the man-hours and filters—for The Apthorp’s fountain is about $1,000. “That’s cheap!” says Mettham. The residents love the fountain and its aesthetic contribution to the courtyard. The sound of the fountain helps the noise and busyness of the city to fade away—and even though the designers back in 1911 wouldn’t have recognized a term like ‘biophilia,’ they certainly knew what pleasure it can bring to an urban space.

A J Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for New England Condominium, and a published novelist. He may be reached at alan@yrinc.com.

Leave a Comment