To be considered an effective manager, one must possess a plethora of skills including the ability to inspire, motivate and handle multiple tasks at once. In the end, building managers are only successful when they satisfy, or better yet, exceed expectations—which can be difficult, especially when interpreting the varied personalities that comprise most condominium boards.

“Every association has its own personality. The policies and procedures that work for one association often do not work for others,” says Steve Cabaniss, vice president of the Management Division at Advance Property Management in Glastonbury, Connecticut. “The manager really needs to listen to the concerns and needs of each community and draw on their experience on how to handle the issues that come up in a way that addresses the needs of the residents without violating the requirements of their documents or state statutes.”

American management guru Peter Drucker sums up proper management in the following way: “The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn’t said.” For many managers, deciphering information and determining best steps to achieve goals often requires seeing the forest from the trees, a quality not inherent in all managers or manager candidates.

“We don’t have the luxury of having one management style,” says Deborah Jones, PCAM, president of the Woburn, Massachusetts-based American Properties Team. “I believe it is up to my managers to take responsibility and figure how to work with the board, because boards change all the time, or every three years. They are our clients. So it’s not about style but communication.”

Inherent Qualities

Since a board represents its residents, the relationship it maintains with its management company is often transparent. For example, the way in which a building operates—from the cleanliness of the lobby to the HVAC system to sanitation services—are all indicators to residents and possible future buyers. Board members often have varied backgrounds and can sniff out managers that are not making the grade. After all, they also live in the building.

“I started as a board member, so I know both sides of it,” says Richard Slater, owner of the Rhode Island-based M & R Connections, LLC. “I dealt with managers that were not straight-forward and after a few years on a board and achieving success with colleagues, I thought I could manage better so I started this business. Our philosophy is simply, protect your property investment.”

Condominiums are a collective investment composed of individuals, some of whom are interested and engaged in community affairs and others that prefer to stand on the sidelines. Regardless of their level of participation they share a common goal which is quality of life. To this end, boards engage management companies to ensure that the property maintains its highest possible value.

With every condominium association having a distinct personality, it becomes challenging for executives to match a manager with a property. “There are a number of variables that go into the assignment of a manager to a property including other property management assignments in the same area, current workload of the managers on staff or particular needs of the property and how those fit with the expertise of an individual manager,” says Cabaniss.

The Proper Training

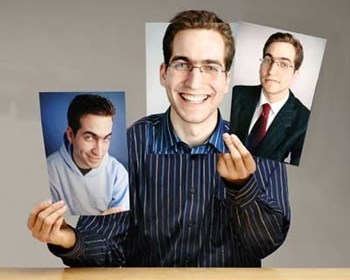

While Jones says she has a “gut” or “instinctual” feeling about managers, she utilizes techniques offered through Everything DiSC Management. The classroom-based training teaches participants how to read the styles of the people they manage. Topics include directing and delegating, motivation, developing relationships, working with other managers and learning how to support longstanding business relationships.

“This program addresses behavioral styles of communication and we have done a lot of work with this,” says Jones. “We teach our managers all the communication styles and how they should interact with people.” She continues. “Everyone—from board members to managers—communicates differently.”

While not all managers are born leaders, there are characteristics that are universal to those who excel at their jobs. However, even the best equipped manager out of the gate still needs fine tuning. Industry experts point to organizations like Community Associations Institute (CAI) for guidance and training.

“Manager training is done in house via an overlap period between a new manager and an experienced manager. Training is also available through the Community Associations Institute, which offers a structured program that result in a PCAM (Professional Community Association Manager) designation,” says Cabaniss. “The Community Associations Institute also offers a variety of classes and training throughout the year that will focus on hot topics of the day.”

CAI’s The Essentials of Community Association Management course provides a practical overview for new managers and review for experienced managers. This course covers:

• Roles and responsibilities of owners, committees, and board members

• 10 steps to developing rules

• How to maintain records for legal support of board actions

• Manager's role in organizing and assisting in board meetings

• Manager's role in preparing the budget

• Seven characteristics of an effective collection policy

• Overview of financial operations

• Characteristics of insurance as a contract

• How to develop effective maintenance records

• How to establish five basic maintenance programs

• How to evaluate your management systems and efforts

• How to prepare a bid request for RFP

Key contract provisions

Recruiting, screening, and selecting people

“CAI offers seminars at their annual trade show with many of the attorneys and other vendors offering seminars to managers and board members focusing on their area of expertise,” adds Cabaniss.

Managers and trustees are also encouraged to attend New England Condominium’s 4th annual trade show, “The New England Condominium Condo Expo and Apartment Management Expo” on May 22, 2012.

Experiences and Results

Executives who have been in the business for many years say in-the-field experiences, coupled with continuing education and training, make for the best managers. Those managers who either disregard board member directives or fail to communicate are easy to point out.

“People that want to become really good managers have to learn to become subordinate to their board’s leadership while leading at the same time, which is a delicate balance,” says Jones. “I train my managers on how best to deliver important messages to boards but also teach them that they have to make the right decisions. They have to be able to bring proper guidance to the board without the board feeling like they are being told what to do.”

Jones is correct in that this approach is a delicate balance. Often times, the message is not delivered with finesse and care and issues arise. Slater explains that poor management techniques he observed as a board member taught him something everyone knows but doesn’t always remember. “Keep it simple, direct and honest. There are managers that will blow all this smoke about this and that. I’m 74 years old and I don’t have time for that,” he notes. “We accomplish our goals by overseeing financial recordkeeping, operating expenses, capital expenditures and reserves to assure financial stability.”

There are instances when a well-trained, adept manager simply does not connect with a board. When this occurs, Cabaniss says he has an open and frank conversation with the board to make sure that the manager clearly understands client expectations. “The manager may often get tips and advice from other managers in the office on how to handle specific issues that are creating the conflict. Sometimes the conflict results from a personality conflict,” says Cabaniss. “In those cases, giving the account to another manager is all that is needed. Positive relationships between the board and the manager are very important for the property to run smoothly.”

Cabaniss recalled a story where a manager was dealing with rules enforcement issues. “We had a manager who was very successful in getting compliance with the rules in a community that is an older conversion with a high percentage of non-owner occupied residents. The manager used very direct and demanding tactics to gain compliance with the rules. When the same manager was asked to perform a similar function at another association, the results were not the same,” he continues. “The reason was the same demanding techniques did not work well in a newer, high end community of mostly owner-occupied residents.” The result, he notes, was a manager change for that association, who employed a softer but still successful approach to rules enforcement.

It is often said that bad news travels faster than good news. Management companies understand they have competition. If executives can’t read their managers and there is a problem afoot, they could unwillingly lose a client due to their poor management.

“This is very much a job of managing relationships. If a manager’s style is too strong and too upfront, the manager might think the board is going along and everything is fine. If the board feels overpowered, they will likely not confront the manager, and the next thing you know you are served with a termination notice and you feel like it came out of left field,” says Jones. “I have had those experiences with managers that are not guiding the board from behind but are rather trying to lead them.”

W.B. King is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment