Unless they're self-managed, most urban residential buildings employ professional property managers to handle their books, bid out repair jobs, hire contractors and deal with the day-to-day administrative functions that few unit owners or trustees have the time (or desire) to handle themselves. The property manager is a key player in a condo building or HOA's day-to-day functioning.

So how do managers and boards of trustees work together for the benefit of their building communities? As with most such relationships, it depends on the manager, the building and the expectations each has for the other. By clearly communicating roles, concerns and expectations, the management /trustee relationship can be a rewarding, functional partnership.

Put It in Writing

Every building community is different—and while certain aspects of running them are similar, there are bound to be points at which buildings differ. A good manager will adapt his or her approach to each building in his or her portfolio and find out exactly how that community wants to do things.

"Some boards like to be told every little thing," says Mark Weisman, president of Boston's Brownstone Real Estate, "and some don't. Sometimes, a board will say, 'Don't call us unless the bill is over $500.' Some don't want to do anything themselves. They may not even want to take their trash out—they want us to pay the bills and keep the place clean and just send them a bill every month."

Whatever your building's preferences and expectations, it's impossible for anybody to carry them out if they don't know what those preferences and expectations are in the first place. To ensure that everybody's on the same page, it's wise to articulate expectations clearly and then commit them to print. In other words, put it in writing.

For example, if your trustees feel that the manager should be on-site at least one day a week to deal with building business, meet with residents and staff, and inspect the property, while the manager feels that one day every other week is adequate, clearly there will be friction unless a compromise is met. By clearly stating your expectations to your manager, then allowing them to explain their own obligations and concerns to you, working through to a mutually agreeable solution and then putting that solution in writing, the potential for misunderstanding is greatly reduced.

It's also important to have things in writing for the benefit of non-trustee residents. If a tear sheet or informational memo is available outlining exactly when management will be on-site, whom to contact in case of an emergency and the schedules for things like trash collection and snow removal, residents will more likely adhere to house rules and regulations. Better still, they may be less likely to complain about lack of communication from trustees/management.

Another benefit of spelling out roles and expectations is that your trustees will have a ready-made checklist against which to compare your management company's performance. Should your building ever opt to change companies, you won't have to reinvent the wheel with the new managers. You can simply present them with a copy, so everyone understands what's expected and there are no surprises for either party.

Reaching a joint agreement about what your building wants in a manager—and what your property manager can reasonably provide—is one of the most important elements of the trustee/manager relationship. With clearly defined expectations, both sides of the relationship can know where they stand and have a good idea of whether or not the relationship itself is working.

Your Manager Works for You

It's sometimes easy for a group of trustees to forget that their building's manager is really their employee—and that they, the board, are the ones charged with making the final decisions about how to run the building. Given that most trustees are volunteers, and not professionals in the real estate industry, informed input from the management is vital—but it's just that: input. The trustees have the final word in the decisions that affect the building community.

To that end, boards and managers must both commit to an agenda for meetings—and an action plan for afterwards—and to do their part to carry out that action plan once the meeting adjourns. That means establishing deadlines for specific tasks, delegating responsibilities fairly and practically and following up to make sure everything that needs doing has been done.

When it comes to handling problems and complaints within the building, trustees and managers must determine who will receive complaints and how they will then be acted upon. Whether it's a complaint committee, a phone hotline, or simply a designated go-to person for managing hot-button issues, the important thing is to establish a system and adhere to it consistently.

"I like to get an e-mail list going," says Weisman, "so I can get in touch with everybody all at once. I know who the owners are, the tenants, the mortgagees."

"You need to be on top of everything," agrees Ed Lyon, owner of Preservation Properties in Newton. "As a manager, you need to set the pace for the agenda. You need to be one or two steps ahead of the trustees, the tenants and the boards."

A good manager with years of experience can be invaluable when it comes to this part of building administration by divvying up assignments and helping individual trustees take on only as much as they can reasonably accomplish in the given span of time. It's also up to the manager to check in periodically with committee members and other trustees to make sure the projects and initiatives decided upon at the meeting are coming along on schedule. While managers are working for their boards and buildings, it's their experience and cumulative wisdom that enables even the greenest trustees to hit the ground running and conduct their community business smoothly.

Manual Transmission

Very often, trustees and residents are both at a loss when it comes to how to deal with a given issue or conflict within their building community. This is where a good property manager again can be a godsend. By documenting and referencing past decisions and solutions reached by the trustees, a manager can assist new trustees and boards in handling new situations as they arise.

One great way to do this is by compiling a procedures manual, says Mindy Eisenberg Stark, an accountant and board consultant based in New York City.

"If your board doesn't have a procedures manual, it would be a worthwhile investment to create one," she says. "Board member training should also be considered as a way to reduce time spent at board meetings and avoid reinventing the wheel every time there is a changeover on the board. Many boards discuss the same issues year in and year out with no resolution, or new members of the board revisit old issues time and again."

Eisenberg Stark says that most board members are professionals in their own fields, but many don't know the first thing about running a large residential building or development. This is where a manager can come in to orient new trustees, refresh veteran board members and even offer training to help the board as a whole become more cohesive and knowledgeable. By training trustees and keeping track of a building community's institutional memory, managers enable boards to move forward without perpetually rehashing the same handful of issues.

Be Here Now

Probably the most important intangible element in a successful board/management relationship is communication: the availability and accessibility of the managing agent, and his or her attendance at trustee and resident meetings. After all, the only way a manager can stay abreast of the goings-on in a given building community is to attend meetings, listen to community members' concerns and work with them in person to resolve them.

Your manager's ability to listen and communicate effectively makes it possible to remedy problems or complaints quickly and professionally before they fester into major crises. Probably the number-one complaint both residents and trustees have about management is lack of communication. By making themselves available, in-person, to discuss problems and offer solutions, managers can go a long way toward reducing—if not eliminating—resident and trustee complaints.

"Communication is the key," says Lyon. "If you're not a good communicator, it doesn't matter what management strategies you use; you won't be a good manager. If you communicate effectively, you can avoid all kinds of headaches."

The trustees' part in resolving conflict should not be overlooked, either. By raising concerns with your manager in a straightforward, respectful way, you can get results without fomenting resentment. Management companies are in the business to make a profit, and they can't do that if they lose clients—it's in your management company's best interest to hear your concerns and address them in a timely and efficient manner.

"You know by a given manager's reputation [what kind of job they'll do]," says Rebecca Marston, a property manager and owner of Boston-based Marston and Voss Realty. "I think word-of-mouth spreads really quickly in this area. People respond to good service—you wouldn't last long as a management company if you didn't take care of buildings the way they want to be taken care of."

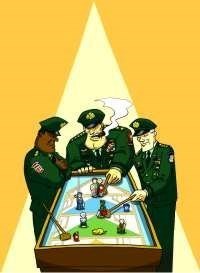

A Team Effort

More than anything else, trustees and their property managers are a team, working for the benefit of their building communities. If each party's responsibilities and expectations are clearly spelled out from the beginning, both are committed to working actively and cooperatively, and positive, workable strategies are developed that everyone can live with, the business of running a condo building or homeowners association can be made smoother and more pleasant for everyone.

Hannah Fons is associate editor of The Cooperator and a contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment