A manager might have to coordinate operations with a single maintenance person or work with any number of doormen, porters, custodians and handypersons depending on the size and nature of the building. When well-trained and motivated, these employees enhance the appeal and ambiance of any property, adding to both the real and perceived value, but excellent employees don’t just show up that way by magic on their first day of work. And even an otherwise great managing agent may not be an expert in the supervision of human beings. Keeping an association staff working hard and happily involves a sophisticated set of communication skills.

Who’s in Charge?

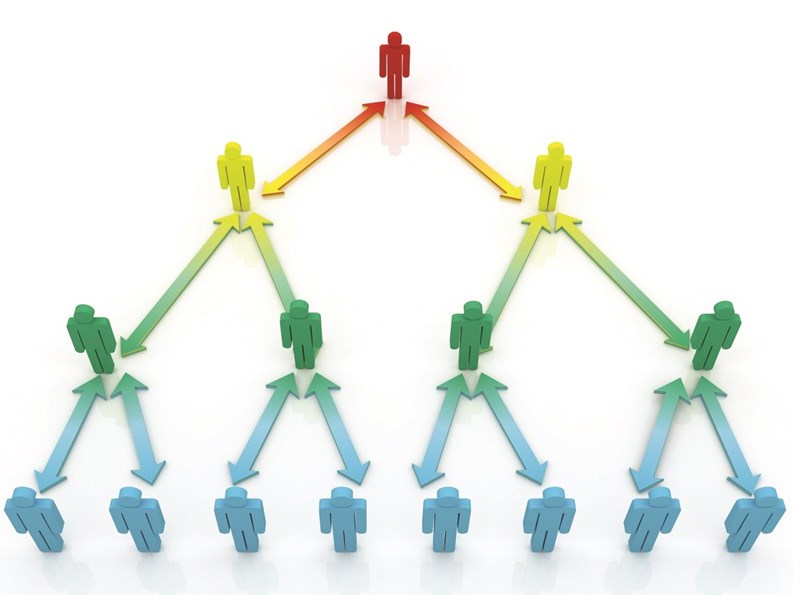

First of all, the board and the association manager both have to understand the supervisory hierarchy. Most association managers agree with the description given by Rick Stern of Sutton Management Company in North Andover, Massachusetts: “The association’s board sets the direction of the property, and the management company carries out that direction. The on-site supervisors make sure all of the maintenance requirements are done according to the specific requirements set by the board and management company.”

Stern divides the tasks of the association manager further into property and asset management. “Property management,” he explains, “is overseeing the day-to-day operations of a property, such as making certain that the landscaping is done, the snow is removed, etc. Asset management examines the physical aspects of the condominium and implements programs that will maintain and enhance the asset. Long-range planning is done for landscaping improvements, painting cycles, capital reserve funding and overall asset values. If there are physical deficiencies, we bring them to the board’s attention with our recommendations.”

Sometimes maintaining a clear line of authority becomes problematic. “Ideally, the association gives orders to the manager, and the manager gives orders to the maintenance person,” states Tony Natale, president of the Greater Rhode Island Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM) Chapter 88. “The board runs the association, and the manager works for the board, but if you have board members and the manager giving instructions to employees, I think that more often than not, you’ll have problems as a result. We’ve run into that too many times, where there’s several people involved in the management of the employee, and it always leads to problems.”

Board members are often tempted into on-the-spot supervision. If you’re sick of seeing a smudge on the wall, and you run into a maintenance person, why not mention it? Says Natale, “If I was a unit owner or board member, it might seem like the easiest way to do it. In a way, you think you’re doing the manager a favor by not bothering him with a minor thing. But if the manager’s in the middle of directing a project, even something small could throw it off. The schedules are planned pretty close. They don't have a whole lot of flexibility. In the morning, an on-site supervisor goes through the property and takes care of issues like that, but if you catch the person in the afternoon and take them away from something else, there could be repercussions.”

And it’s not always board members who skip the manager and go directly to the employees. Natale says, “It might be a beautification committee or a landscaping committee member. It’s an owner that is in a position of authority, and they go around the normal communication chain.”

Telling employees to let the association manager know when they’re asked by someone else to take care of a problem will help. “But first,” says Natale, “before we even get to that, we have a conversation with the board and/or any committees that may be involved, just to make sure that they understand what the flow of information should be.”

On the other hand, Marian Servidio of Park Place Management in Burlington, Vermont, has a different perspective. “We find that the board will sometimes intervene,” she says. “Our office is not on site, but the board members live where the on-site staff work, so they will interact will them. If there is a sensitive matter, the board members will consult with us or request that we manage the issue with the staff.”

Communication Is Critical

Communication between board and manager so they’re in agreement on how things are run is clearly crucial, and communication is one of the keys to dealing with employees, too. “The first tool you need,” says Natale, “is a job description, so the employee knows exactly what he is responsible for. The second tool that I think is critical is continued communication between the manager and the employee so that there's an open line of communication going both ways.” He continues, “You need to develop a personal relationship with each person. We’re not overseeing hundreds of thousands of people, so we’re able to build a relationship with a new person so that they feel they can come to you with issues, and then you can go to them when there’s a problem or something that needs to be resolved. I found that each individual’s a little bit different. Some require a more hands-on process, where you need to talk to them regularly and go over things that they’re doing on a particular day. And then others are a lot better at managing their own time, and they don’t need as much hand-holding. So it really depends on the individual. And you only get to know that after working with them. At the beginning, I probably hand-hold everybody until I get the comfort level that a certain person is able to do things the way they’re supposed to be done, without that level of intervention.”

Stern concurs that communicating with staff is vital. “The most important thing when it comes to managing association employees is communication . . . . Employees of Sutton Management Co., Inc. carry iPhones so that communication between the office and maintenance is immediate. In addition, the smart phones allow us to take pictures and document violations, repairs made and repairs needed.”

Communication is essential to Servidio as well. Among her top three elements necessary to successful association staff management, are “regular oversight and inspections of the property and the work, discussing with the personnel what challenge they are having in completing their jobs, and when necessary, “advocating for the staff and reminding residents of their responsibilities.” She elucidates, “Expectations of owners and residents versus what the job description calls for is the biggest challenge we face. Owners expect a lot of on-site staff.”

It helps to have everything in writing—the job descriptions, of course, but Natale also suggests the same approach to special projects. “Give them the specifications in writing. It just reduces the chance of error.” He also suggests an occasional meeting with all parties—board, manager and employees. “Just to talk about the kinds of things that the employees are doing on a regular schedule and the kinds of conversations the manager and the employee are having.” Stern advocates regular reports to the board, which “should be updated by the property manager once a week for all non-emergency maintenance and immediately when emergency or maintenance problems arise.”

Problem Solving

Even routine maintenance can become a problem due to absences. Says Natale, “Scheduling can be difficult when you have a small organization, and more often than not, a condo association has only a manager and the maintenance person. When the maintenance person isn't around, it makes it difficult unless the manager has a plan for how to deal with absences. If you have a good management company, it will have other employees that can fill in, so that when the maintenance person is away, whether it's a planned absence or something that comes up as an emergency, there's a plan in place to make sure the property's covered.”

Another common problem is theft. Stern gives an example. “We are always very conscious of theft. We discourage any association from handling vending-machine revenue. The opportunity for theft is great. We always use bonded and insured companies to collect the proceeds from laundry machines. We took over a 250-unit complex where the board had for years used a private appliance vendor to collect the money from the laundry machines. This company was also responsible for repairing the machines. One of the employees was collecting money on Sundays without the owner’s knowledge. Since they repaired the machines, the employee had a set of keys. The loss was almost $10,000 a year. Since we have taken over, we have a publicly traded, national laundry company collecting the money and repairing the equipment. The revenue went from $9,600 annually before we took over to about $19,000 annually now.”

Resources for Continuing Learning

Association managers have various sources of information and help at their disposal. Natale says, “Usually the management company you work for would have resources for dealing with staff. And the Institute of Real Estate Management has manuals and guidelines that managers can use to help them in all sorts of different situations.” Servidio suggests the Community Associations Institute’s resources, “whether it’s seminars or workshops or the periodicals with a wealth of information.” And she says, “We also discuss physical-plant maintenance issues with contractors and get their advice, as well as researching online.”

The workforce, staff, human capital, no matter what the name, it all comes down to “people power.” In regard to managing the people who service and maintain an association, Stern says his simple but best advice is to “treat your employees the same way you would want to be treated. If you do that, you will have happy employees.”

Anne Childers is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment