From the outside, the structure of a condo, co-op or townhouse building may appear to be monolithic; just pieces of brick, steel, vinyl or wood, punctuated with some glass here and there. That's an oversimplification, however. A multifamily building is perhaps more like a human body, with a multitude of organs and moving parts working together to keep the building healthy and vibrant. From the roof to the boiler and all points between, ensuring that systems are operating efficiently is a continual challenge.

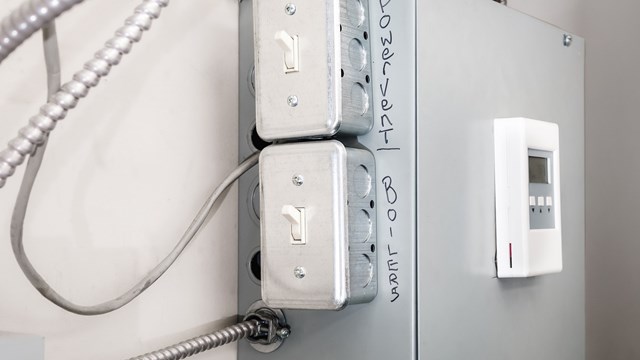

The primary operating systems in a multifamily building include roofing, the building envelope, waterproofing, electrical, mechanical, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), plumbing, and in some cases, elevator systems. In high-rise or multi-unit buildings especially, the association is responsible for providing many of these basic utilities to unit owners.

Experts say there is no standard maintenance plan, since mechanical systems in New England residential buildings vary widely, reflecting the wide variety of building ages, and wide—some would say wild—variations in weather. Certain regional trends stand out, however.

Lynn Sallee, reserve study specialist with Facilities Advisors, Inc., in Marlborough, Massachusetts, observes, “We deal mostly with older buildings, and they will typically have forced hot water heating systems, often with a master boiler. In New England, oil has been the standard, besides being low-cost (in the past) but mainly because it’s easier to transport than natural gas, which requires buried lines.” Getting lines installed underground is a real challenge in this region, he points out, because of all the ledge lurking just below the surface or “boney” (boulder-laced) glacial outwash.

“In addition, air conditioning in old buildings amounts to window units or portables. By contrast, in new, more upscale buildings, you find all central air with ductwork” to all the living spaces, he notes. “In cold months it’s forced hot air from one or more master boilers, using natural gas where available… In hot months the process is reversed and air is run through a chiller—like a big air conditioner. In smaller buildings, you’ll probably see heat pumps, mounted outdoors or on the roof.”

Basically, a heat pump is a transporter, moving heat energy from one place to another, depending on the season. Heat pumps save on fuel because they utilize the thermal energy in the air. Even in air that seems cold, heat energy is present. When it's as low as 40 degrees outside a heat pump extracts this outside heat and transfers it inside. When it’s warm outside, it reverses directions and acts like an air conditioner, removing heat from the interior. In the north, heat pumps are mainly used for air conditioning with a supplemental heating system.

Electricity fuels the climate control in about a fifth of new buildings, Sallee states, since it has become more cost-effective with weather-tight construction and ever-thicker insulation One recent development in new residential construction, he adds, is that “today you don’t need to wire buildings for telephone lines” even as cable, fiber-optic and other delivery systems continue to evolve.

Maintenance Starts at the Top

Beyond mechanicals and utilities, the biggest, most costly issues for building maintenance, “are the big four,” says Ralph Noblin, consulting engineer and principal for Noblin & Associates of Bridgewater, Massachusetts. “These are roofing, siding, decking and pavement…. and in recent years, roofing is pulling money from the other three.”

“Historically,” he explains, “roofs were let go for too long. We’ve seen a dramatic shift in priorities, with the integrity of the roof becoming a number one issue (for managers). Besides the obvious physical damage, it’s become clear that if leakage is allowed to continue, mold results.”

In New England, a major cause of roof leaking is ice damming, and “the major cause of ice damming is sustained cold, like we had last winter,” says Noblin. “It was similar to the winter of 1993-94, which was a real wake-up call for the entire industry. We had heavy… and sustained cold, and up on the roof it may be 40 degrees under the snow, causing a little insidious river running under the snow and freezing at the roof’s edge. Now that eventually turns into big block of ice” growing and backing up under the shingles.

Noblin points out that a products are available that provide ice and water shield, in the form of a three-foot wide liner coated in a gummy material. It is installed under the shingles at the roof edge and prevents water from seeping into the roof deck from beneath the shingles. In addition, water can’t leak around the nail holes because they’re sealed by the gummy quality of the shield. This works much better, he notes, than the asphalt felt that is typically used under the shingles to line the roof deck.

Building codes vary from state to state, and even locally by county or city, although many are based on the IBC (International Building Code). Noblin says, “The code (IBC) actually calls for the water shield fabric to cover 24 inches from the inside wall with one inch of overhang… but building codes are very slow to catch up with the real world (of building construction). We have been specifying two rows of shield to create a barrier almost six feet wide. We’ve gotten (a major, national) home construction company to change their specs for roof-edge water shield to six feet wide, from Pennsylvania north.”

One issue for communities, Noblin continues, “as opposed to single-family home construction, with large-volume condo projects with dozens of units constructed at the same time, building materials may not be of the highest grade.”

When considering siding along with roofing, the integrity of a building’s shell is important for reasons beyond protection from weather. Basically, looks matter. “Realtors tell us,” Noblin adds, “that prospective homebuyers take about eight seconds to make a decision about a property after the first glance.” If siding is neglected it takes a toll on property values—right away. Noblin points out that it’s not simply the quality of materials to consider, but proper installation. “We’ve seen neighborhoods of three-deckers, freshly updated with vinyl siding, and strips (of it) would start blowing off because the contractor nailed the new siding to the rotting wood clapboards underneath. So… they’ve learned to rip off the old siding first.”

Condominiums, Noblin contends, face a unique challenge in upgrading the exterior shell. “What can the trustees do about windows and doors, which are generally owned by the unit-owners? You can’t put new siding around old windows with rotted openings.” A new siding upgrade requires a cooperative effort, enlisting homeowners to replace sub-par windows and doors when the association is having new exterior surfaces installed.

In New England cities, sprawling brick mills—often along riversides—dot many urban landscapes, and huge, old, factory buildings are often re-purposed into residential units. “Developers are asked to create luxury ‘loft’ housing in buildings that were never watertight to begin with,” notes Noblin. The “shell” of these buildings could be made more weather tight, he adds, “but there’s a reluctance to disturb the historic ‘look’ of the outside architecture, so they may continue to leak…” so even though the interior is rehabbed “they still need more work on the outside to make them livable.”

In modern buildings, Noblin states, the envelope is so airtight and insulated to conserve energy, “that when things get wet, they either never dry out or dry out really slowly. The way I define leakage, is whenever water gets beyond where it’s supposed to be. With new construction, there’s a lot of layers between the exterior siding and the interior wall, so there’s plenty (of stuff) there to sponge up leaks” before anyone notices a problem. “Then you have all the ingredients for the growth of mold—the right temperature, moisture and food.

“I’m convinced,” he says, “We may have more mold in the air, here in the Northeast, than years ago. The black stains that develop on roofs are very common down south but they’re showing up here more often.” Fortunately, it’s manageable, Noblin explains. “Surface mold can be cleaned (from roofs and siding) with a bleach solution and low-pressure power wash. You’ll notice that mold is usually absent on the downslope from chimneys. That’s because the flashing (around the chimney where it touches the roof), whether it’s zinc, copper or lead, prevents the growth of algae. So one option is to install a metal strip along the roof ridge.” The strips, manufactured with zinc, for instance, when rain-washed, send zinc carbonate down the roof. It won't kill algae that already has a foothold, but it stops new growth.

Maintaining a High-Rise ‘Lifeline’

For multi-story residential buildings, one feature that always needs attention is the elevator. Paul Ahearn is president and owner of New England Elevator Consultants in Boston. He points out that “laws concerning elevator installation and maintenance have evolved because of accidents, stemming from mechanical failure. The most frequent mishap is people tripping on a mis-leveled sill,” he continues, but much worse accidents can and do happen. “People have been crushed when the doors stayed open while the cabin moved (vertically).”

“People get hurt through negligence on somebody’s part…,” Ahearn states, “when proper equipment wasn’t installed or put in correctly. Most of the time it’s due to building owners or managers cutting corners.” Plus, if an elevator in a high-rise needs repair, it may be out of service for days or weeks—not a good situation for an elderly resident on an upper floor. “There was a high-rise in Revere (near Boston) that was shut down for repairs,” he relates, “and the building owner had to put up some of the residents in hotels for the duration.”

Ahearn says that even though “state laws may require annual inspections,” it would not be prudent to rely on inspection certificates to assume an elevator is in safe working condition. As he explains, “In Massachusetts, there are only 17 elevator inspectors for almost 400,000 elevators, so it’s virtually impossible for them to keep up (with the inspection schedule). It’s a system that could be privatized and be more efficient.”

Linda Stearns is senior property manager at The Niles Company in Canton, Massachusetts. She has also had experience with elevators that had to shut down for repairs. “We had 180 units in two six-story buildings… the property was 100 years old, with an elevator that needed some new parts, so it was not operating for about 10 days, but only one resident needed to move into a hotel during that time.

“I’m big on preventative maintenance,” she continues, “especially when it comes to 100-year old elevators, but sometimes, all you can do is react and take action when something breaks. You really can’t always see behind the scenes… to pinpoint something that’s about to fail.”

One successful project she was involved with at an older property resulted in a huge savings on fuel cost. In a Boston suburb, says Stearns, “we had a condominium community that we converted from underground oil tanks to natural gas, installing a connection up the street to the main gas line. This property is unique in that the association provides central air heating along with hot (and cold) water, as part of the unit fees. We also installed new boilers in each building, but the air handlers and ductwork inside individual units were 45 years old… but we are moving toward putting new condensers on the outside.”

“We have seen return on investment already with the (fuel) conversion,” she reports, “but considering that almost all homeowners’ utilities are included, the fees just haven’t been high enough to cover everything… but we’re working on that.”

Stearns agrees that “every building is different, so when we take over management of a new property, as any good property manager would, we immediately order a reserve study which will itemize each system and piece of equipment along with its lifetime. I ask the board of directors to hire an independent engineer, which may cost several thousand dollars, but it’s well worth it, and I can then present (the report) at an annual meeting,” to make sure unit owners are informed about what’s needed, and what to expect.

Marie Auger is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment