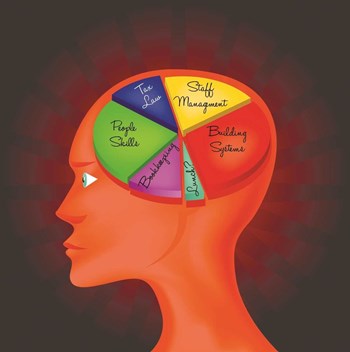

Property managers are known for wearing many hats, and are expected to be expert in some very diverse topics. Few of them, however, train for and begin their careers as property managers; most came into the industry from other fields. Managers can be anything from ex-teachers to ex-electricians, and often admit to picking up skills “on the job.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but today’s association boards and management companies expect professional managers to meet professional standards, and experts agree that those standards require at least a basis of formal education or training.

Paul DeGennaro, owner of Ingleside Associates of Fairfield, Connecticut, notes that educational programs for property managers have generally been provided by real estate professional organizations such as IREM (Institute of Real Estate Managers) and community association groups, especially CAI (Community Associations Institute), and “there has been some competition between the two.” He notes that several years ago, “Connecticut instituted a certification requirement for property managers. This is an incredibly good idea,” although certain aspects are still being ironed out. “We’re working with the legislature to understand the differences (among educational resources),” he adds.

The law in Connecticut states, “Any person who provides management services is required to register with the Department of Consumer Protection and submit to a state and national criminal background, complete a nationally-recognized course on community association management, and pass the Community Association Managers' International Certification Board (CAM-ICB) Certified Manager of Community Association (CMCA) examination.” The other states which have passed laws and regulations governing the practice of community association management include: Alaska, California, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Nevada and Virginia.

Even given such stringent requirements, DeGennaro contends, the criteria for being a good property manager goes beyond education or experience. “Regardless of (managers’) backgrounds… more importantly, are they honest, and ethical, and do they know what they’re doing? That’s where education fits in, but honesty and ethics are really the most important. It’s the combination (of) doing the right thing and doing the thing right. The financial responsibility, especially, is really a personal trust… you’re handling funds for all those unit owners… They’re paying fees each month and depending on the manager” to watch over their interests and investments.

There are several resources, both informal and formal, that managers can use on an ongoing basis to stay up to date on industry trends and best practices. Among them are networking events where managers can share ideas, problems and solutions, and, of course, publications like New England Condominium. On the more formal side are seminars, webinars workshops and career-track courses that lead to the professional designations or accreditation.

Law firms, industry tradespeople and organizations provide informal “lunch and learns” for community association management personnel with information on topics within the industry as a service to their existing customers, to companies they hope will become their customers, and to professionals within the trade associations. IREM, for example, recently offered managers a seminar on Boston’s Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance, and attorney Frank Flynn led an IREM training seminar on “Important Do’s and Don’ts for Property Managers.” And both CAI and IREM regularly offer formal courses leading to certifications like CAI’s Professional Community Association Manager (PCAM) and IREM’s Certified Property Manager (CPM) designations.

Colleges have also opened the doors to those intersted in careers in the industry. Among them is Curry College in Milton, Massachusetts, which offers Residential Property Management as a concentration within its Business Management degree program, and a property management certificate program that’s available on a part-time basis with evening classes.

Even given the huge responsibility and need for technical expertise, DeGennaro points out, “the majority of people doing property management… did not go through any sort of education. They come from every possible field. There are good people working in the industry who may or may not have the credentials.”

Plus, he notes, getting trustees to pay for education can be a tough sell, especially since it’s the professional manager who has to explain to board members what they should be spending the association’s money on. “In practice, funds are often so limited, trustees are reluctant to pay for a manager’s education. In fact, trustees should be taking courses themselves but they fear that unit owners might object.” The investment in a board’s or manager’s education, he adds, offers long-term value and a leaner, more efficient operation—but it’s still a hard sell.

DeGennaro insists that managers need education to learn the “how to” part of the job, but it must be based on a core of ethics. “Educational credentials are valuable and necessary, but not sufficient, in and of themselves. There is still no substitute for board members paying attention to their manager’s behavior… You must always supervise the people you hire.”

Following the Path

James Shope, PCAM, is community manager for The Dartmouth Group in Bedford, Massachusetts, and has worked for many years at The Village of Nagog Woods in Acton. He observes that “most managers are in the field a long time before getting PCAM certification. I started out (in the early 1970s) working for the developer of Nagog Woods,” as construction was wrapping up and units were being sold.

“I was responsible for completing those final ‘punch list’ items for the homebuyers. I worked in maintenance, then became the maintenance foreman. At the time, the association board president and I started looking into courses available through CAI. I began, on my own, with the M-100 courses which provide a basic overview. The topics include pretty much everything that a manager has to deal with, including budgets and financial operations, facilities maintenance, insurance and risk management, contracts, governance, ethics and legal issues.”

The CAI courses supplemented Shope’s already broad knowledge base, since he had been doing the job right along. “A lot of the stuff I’ve done is self-taught, and I’ve had business courses and accounting (at a community college). The financial software, for instance, keeps evolving. Early on, one of my board members actually wrote a program for me to use for the property’s finances, and we have used Peachtree… other programs can be used, QuickBooks or Excel.

“After completion of the M-100 series, and passing the tests, there are M-200 series, which is six different classes, about two days each. They build on the M-100 courses, adding more technical subjects like ‘depreciation of capital equipment.’ These CAI courses are offered regularly all over the country, although a few are available online. I took them when they were offered closest to home, which meant anywhere from New Jersey to Maine, and beyond. Taking classes in person… it really helps to interact with instructors and your peers.”

The M-series of classes is just one part of the process towards earning PCAM designation. “You also need at least five years’ experience” in the management of condominiums, Shope points out. “You also can earn points, in addition to class time. For instance, I wrote a couple of articles for the CAI magazine. You can earn points for college credits, or service on the CAI board, presenting lectures, that kind of thing.

“After meeting all those requirements and earning enough points, you apply to CAI to take on a ‘case study’ of an actual property, which is similar to completing a thesis,” says Shope. “The classes give you the tools to prepare you for it. Different communities ask to participate and offer their properties to be the subject of a case study… It’s a huge bonus for an association board, as the resulting report or plan would be very expensive if it came from a consultant. I was accepted to do a case study at a community with hundreds of units in the Washington, D.C. area. There was about a dozen of us assigned to this case study from all over the country. Over a two-day period, we met with key people who were available on site… board members, vendors, management staff, who gave us tours—and we went around the property on our own as well. There was so much information, I dictated everything into an audio recorder. You’re expected to cover everything in the six major topics, reviewing things like administrative procedures, legal documents and insurance. You have to analyze how the community is doing everything and determine what is adequate, or lacking, then you come up with a plan for improvements. Even in the best-run properties there’s always a shortfall somewhere.”

After that intensive two days, Shope continues, “You have 30 days to submit a final plan to the CAI board, which then issues either a pass or fail. One thing I did was create a disaster plan with very detailed procedures for identifying risks, mitigation, standards, timetables and resources for recovery and clean-up—it was very comprehensive.

“After my case study was approved, I was awarded the PCAM designation and went to a CAI conference in Denver, to attend a ceremony to accept it. The entire process took me almost 20 years, because there were periods when I took time off from classes and course work. The whole process could probably be completed in about two years, but a lot of associations cannot afford the almost $1,000 needed for just two classes.

Study Never Ends

“To maintain the designation,” Shope, adds, “I must meet recertification requirements every three years. This means completing some M-300 level classes. You must meet some pretty high standards to earn a PCAM. It gives you a base of knowledge that can be quantified. It’s a plus for management companies especially to have qualified PCAM staff on board… It gives them credibility.”

Frank Rathbun is vice president of communications and marketing for CAI’s national office in Falls Church, Virginia. He insists, “An educated manager is a better manager. They are using CAI designations all around the world. If you want to build a career in this industry, this educational path is what you do. These days, community associations are looking for the best, most professional management they can.

“Plus, you have to re-certify for most designations,” he adds, “because the industry’s ‘best practices’ change, laws change, requirements change. You want a manager who stays abreast of updates in the business.”

He points out that there are many specialized designations and levels of education that can be earned at a pace that boards and their staff can manage. Certifications can supplement each other or be taken in anticipation of a PCAM. “Besides individual managers, even management companies can get accredited,” he notes.

Rathbun acknowledges that getting a manager off-property and away from the duties that never end is a challenge for associations, especially when education is sometimes perceived as “time off.” But boards still need to see the intrinsic value. “We know there’s an advantage to the classroom experience, such as networking and sharing information with peers. However, we have worked hard to get these courses online to make them more convenient.”

”When managers have designations,” he contends, “it tells you a lot… that they’re committed.”

Marie Auger is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment