The media and political buzz surrounding so-called 'homeshare' or 'short-term rental' websites (primarily Airbnb, but also other similar services like Homeaway.com and VRBO.com, just to name two) has been on the upswing over the last year or so. It sounds like a perfect arrangement; You go on vacation, and rent out your home while you’re gone—you get a house sitter who pays real money, instead of the other way round.

Or, you stay home, and rent out your spare room—making a few hundred (or even a few thousand) dollars without doing anything more than washing your extra set of sheets and wiping down the counters. It’s all part of a growing trend called homesharing, which is taking so-called 'destination cities' by storm.

An Ideal Idea?

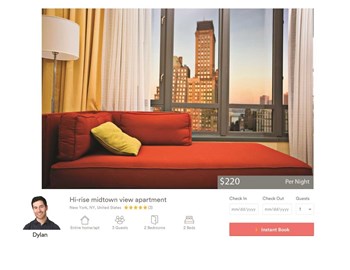

Homesharing is especially popular—and controversial—in major cities like Boston and New York, where rents are ridiculously high. In Beantown, for example, you can rent everything from a luxurious penthouse apartment complete with a private roof deck and Jacuzzi in the North End of Boston for $200 a night to your basic comfy couch in a room in Somerville for $30 bucks a night. Indeed, for renters and for those doing the renting, when it comes to homesharing, the sky's the limit in terms of what you can get for your money, and how much cash you can make.

But while thousands of apartment owners in cities like Chicago, New York, Boston and San Francisco love being able to monetize their units by renting an extra bedroom (or even their whole place, if they're out of town) to a visitor or tourist, condo and HOA boards and management are typically less enthused about the trend. A constant stream of non-resident visitors raises security concerns, adds wear-and-tear to common areas, and complicates the enforcement of house rules. Depending on the city, short-term rentals may also run afoul of zoning and hospitality laws.

Homeshare History...and the Law

The biggest player currently in the homesharing game is without question San Francisco-based Airbnb Inc. Founded in 2008, the service allows anyone to list their house, condo, spare room, couch, boat, treehouse or any other living area for short-term rental. More than 9 million people in 34,000 cities have checked out Airbnb—with more than 500,000 listings across the world—so this trend is certainly not shrinking or going away.

In fact, according to the company, on December 31st, Airbnb had its biggest night in history of the company, with nearly 550,000 travelers using the company to stay in more than 190 countries. Of those, 91,000 were guests using Airbnb for the first time, and 22,000 hosts were new, too. That’s compared with five years ago, when only 2,000 people used Airbnb on New Year’s Eve.

According to Braintree, Massachusetts-based Marcus, Errico, Emmer & Brooks’ attorneys Mark Einhorn, Matthew Gaines and Alex Levine, Internet-based services like Airbnb can create a firestorm of problems for association boards, management, and homeowners alike. They recently received a number of phone calls seeking advice on the issue.

“Local and state governments are also grappling with the questions raised by transient uses of residential properties,” the attorneys wrote in a recent column. “Like association boards, government officials are trying to balance competing interests: On one side, homeowners want to rent their properties and governments want to encourage innovative businesses (and collect tax revenue from them); on the other, neighborhood residents find strangers in their midst uncomfortable. As one New Yorker explained to the New York Post: “When you come home at night, you don’t know if you’ve got a trick, a poker game or a cocaine deal going on next door.”

Like many communities, Boston is trying to decide how, if at all, to regulate owners who are renting their homes, or rooms in their homes, like hotel rooms. The Massachusetts Department of Health and Human Services has suggested, the attorneys said, that they should be regulated like bed and breakfasts and required to pay an annual fee. But Boston’s Director of Inspectional Services issued a memo in the fall of 2014 directing his staff to take no action against owners who fail to register until city officials determine “how these services fit within our existing zoning and permitting definitions and whether new or amended regulations are warranted to address these specific arrangements.”

Popular...But Not Really OK

Legal or illegal, several courts have weighed in on the issue with varying results, the attorneys said. But as far as condos go, transient uses are forbidden. “Many condominium documents either specifically prohibit transient uses or establish minimum rental terms―6-to-12 month minimums are common. If the community’s documents don’t contain this provision (and many do not), one obvious solution is to have owners approve a master deed or bylaw amendment adding it. We suggest establishing a minimum rental period of no less than 30 days. You might also specify that owners must rent their entire unit, not just portions of it. This would preclude an owner with a three–bedroom unit from renting the two extra rooms to paying overnight guests,” the MEEB attorneys said in their column.

If homesharers get caught, the penalties may be severe, including fines and possible evictions.

The popularity of homesharing is matched only by backlash against it. Last year, illegal hotel complaints―like Airbnb and other short-term rental places—increased 62 percent. Still, it’s all about the money, and Airbnb is big business. Take New York City, for example. A report from New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman found that 6 percent of the hosts were responsible for 36 percent of private bookings that were worth a whopping $168 million—or 37 percent of the revenue.

And many of the listings proved to be illegal as well. Schneiderman found that as many as 72 percent of Airbnb reservations are illegal. And that illegality extended to the courtroom. In January of this year, a New York City housing court judge evicted a rent-stabilized tenant for using Airbnb to profit off of his rental while he and his family were living elsewhere. It is the first recorded case of someone being evicted for using the service.

It doesn’t look like they’ll stop any time soon but the government is catching on.

Up until February 15th of this year, Airbnb was blamed for not collecting hotel taxes from many of its hosts–and for essentially allowing its members to use their apartments as ad hoc hotels, taking away business from real, legal hotel businesses. Last year, Airbnb began collecting taxes in San Francisco, Portland and California, and they’re extending the practice to more cities, including Chicago and Washington.

Legal or not, lots of people are using Airbnb and similar vacation rental services, regardless of whether or not they own their own building, own their own unit or just rent.

Most are doing it because this is such a lucrative and seemingly easy way of making money.

Nevertheless, people are still probably taking a risk. Buildings often permit 30-day leases, but doesn’t allow anything shorter than that. However, short of checking everyone who enters the building, it’s difficult to discern whether someone is using Airbnb.

“No one would advertise it, so you would never know,” says one attorney. “It probably has happened here, but who knows?”

Most property managers say that they don’t allow homesharing or short-term leasing, but that in small buildings, it’s very hard to tell whether someone is doing it. One manager spells it out plainly: by renting out their unit—whether condo, co-op, or rental—or even just a bedroom via Airbnb or some other homesharing company, a resident can potentially cover their rent or common charges, and make a tidy profit as well. That’s why the concept is so successful, and that’s why so many New Englanders are willing to take such a huge risk by letting strangers live with them, or occupy their home in the host’s absence.

If You Insist…

Manhattan real estate attorney Adam Leitman Bailey says that there are a few ways to stop homesharing in your building community if you don’t want it to occur. If you see people constantly coming in and out of a given apartment with suitcases, then that’s a sure sign that the owner or legal tenant is renting via a homesharing company.

“If you’re on a board and want to stop Airbnb, you should stop people from going upstairs,” Bailey continues. “Don’t let strangers go into the building unless the owner is there.” Bailey does admit that “If they say they’re a cousin or an uncle, however, it gets a little fuzzier.”

The MEEB attorneys agree with Bailey about short-circuiting the issue or by strictly enforcing your current rules. “If your association can’t prohibit short-term rentals, or chooses not to do so, you should manage them as you do rentals of any kind: that is to say, by making the unit owners responsible for any problems created by their “guests” or tenants. If tenants disturb other residents or violate the association’s rules in any way, insist that unit owners deal with the problems, and fine owners who fail to do so. Substantial (and repeated) fines combined with the disapproval of their neighbors may make the ‘my-house-is-a-hotel’ business less profitable for owners—and considerably less appealing for them.”

Undesirable as homesharing may be for a condo or co-op building, the reasons why owners participate in it can be just as serious. Perhaps the person doing the renting is desperate because they’ve lost their job, or just had some other huge or unexpected expense.

“They’re unable to pay their bills, and homesharing allows them to pay their mortgage,” Bailey says.

In some very expensive cities around the country, that’s very compelling. But the last reason to forbid homesharing in a co-op or a condo, and to eschew the practice as an owner, is that on top of the possible $1,000-a-day fine, the person renting out their apartment can get evicted and foreclosed because they could be violating terms of their lease, Bailey says. “I have tons of cases like this,” he says. “It’s huge.”

And it’s not going away anytime soon.

Danielle Braff is a Chicago-based freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment