Nothing lasts forever, and though you can’t predict the moment a piece of building equipment will break down, you can prepare for it. Even the toughest boiler, HVAC unit, or elevator will eventually tucker out and need major repairs, or just give up the ghost and have to be replaced. And with New England’s penchant for hot summers and cold winters, parts of a building sometimes must be replaced more frequently than might usually be expected elsewhere in the nation.

That’s why working estimates of usable life spans of various building systems can be very helpful to management when planning short- and long-term budgets and capital improvement projects. For some communities, these estimates are a part of a regular evaluation of the facilities. Whether or not this evaluation is a part of your community’s management process, knowing about the life spans and maintenance needs of your building’s systems should be a part of your understanding of your community. Having such knowledge can help you prepare for the worst and in doing so, also help you save her money.

Finite Lives

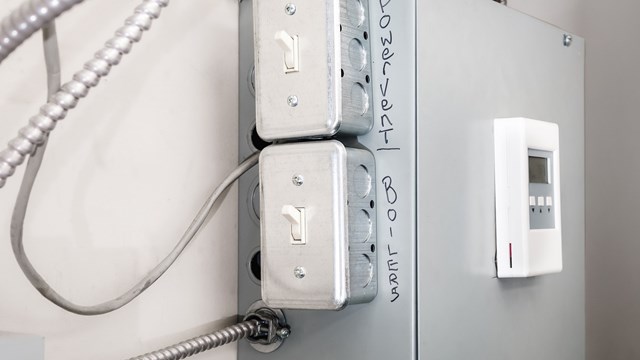

The longevity of any building system depends upon factors including the type of system, be it the roof or the windows or the elevators or the plumbing, how often it is used, how old it is, how well it’s been cared for, and even the effect of weather. It’s axiomatic that the best-run buildings will have every pump on every system labeled, and a record kept of each servicing and replacement of every part on each piece of equipment or building system.

Generally speaking, hot water heaters in multi-family buildings will last for just a decade or so. The life spans of HVAC components vary depending upon the type of system, but usually they will last for 15 to 30 years. Trash compactors get some of the worst resident abuse, being used for things they shouldn’t be, and often last for only 8 to 10 years. Major plumbing components can last 50 to 60 years, but when they are close to the end of their life, management should plan for the fact that the equipment will need to be replaced.

In New England, the housing stock in condominium communities varies enough to affect the conversation around HVAC systems. “In general, there are any different kinds of HVACs. There are some that are suitable for a standalone residential unit. There’s obviously a totally different system for a high-rise. When you’re talking about residential units, usually the bylaws are written up so that the unit owners are responsible for their own heating systems or air conditioning systems,” says Jack Carr, senior vice president at Criterium Engineers in Portland, Maine.

It’s a typical refrain in business and property management that the more you spend now the more you save later, and that goes doubly so for HVAC units. “With today’s energy standards and the cost of oil, with a typical residential condominium heating unit, the payback period is probably less than five years if you’ve bought a new HVAC system. So a 15-year old unit is relatively inefficient. People are shocked to hear that. That’s the tremendous strides that have been made in efficiency in the last few years. And if you’re going to gas from oil, it’s even less time,” says Carr. That’s right. It’s conventional wisdom that the more attention and upkeep you give to something, the longer it will last. But tender, loving care does not go as far with HVAC units, since efficiency standards have changed so drastically in the last ten years. Since those new systems have different designs that are more difficult and costly to repair, they don’t last as long as some of those old 100-year old boilers, some of which are still around, albeit repaired over and over. But, that new- fangled system is so much more efficient that it pays for itself within just the first five years, says Carr.

Elevators typically last for 30 to 40 years, with proper maintenance. “It’s just one of those things where 30 to 35 years it stops being worth it to keep it along. Elevators have service contracts that take care of maintenance for a while, typically 20 to 25 years, but after that you’re going to after replace it at a certain point,” says Daniel Isles, senior associate at On-Site Insight in Boston, a company that does capital needs analyses and energy audits.

Carr says that even though we think of elevator use as pretty straight forward, their wear and tear can definitely vary building-by-building. “What you’ll find is some high rise condominiums that have a lot of turnover because it’s a lot of rented units. Those elevators get abused more than elevators that have unit owners. Unit owners just use them on a regular basis. But because people are moving their goods up and down the elevator, they stick furniture in there to keep the door open, and I’ve seen those kind of elevator units fail in more rapid ways,” says Carr.

Roofing is one the most carefully inspected part of a building in reserve studies. Obviously, it’s a very important part of a structure, but a poorly-maintained roof can lead to all sorts of horrible, costly issues. “No matter what material we’re looking at, it’s one of those 20- year time frames. They have 30 year shingles, 25-year shingles, but we’re always kind of looking to 20 to 25 years” in reserve studies, says Isles. “It’s one of those things that can vary drastically depending on the weather conditions. If they lots of standing water on the roof, that’s a huge. Moisture is going to have a huge impact, as well as sun exposure. If it’s really shaded, north facing, you’re going to get a lot of organic growth on there. On the other hand, a roof that gets a ton of sun there’s going to be UV damage,” he says. Experts recommend that roofs of co-ops and condos be checked at least annually for any defects, holes, leaks or any other problems. All problems should be immediately fixed, before they become major problems. What material you use can make all the difference in later maintenance costs with roofing. “There’s different grades of shingles, the 20 year warranty, the 5 year warranty. You can buy a heavier shingle which will have a longer warranty and will last longer,” says Jeanne Allen, AIA, principal at Kipcon New England in Boston.

And while they may not seem like a building system per se, building exteriors are crucial to maintaining the health the building’s structure. Concrete foundations and exterior structures like balconies need to be monitored over the years. “The snowball effect of getting a little crack, can contribute to more water infiltration. We usually look at a brand new brick elevation, if it’s well done, it can last a very long time. You’re not even really going to have to touch it for 10 or 15 years when you have to do caulking work. Down the road a ways, anything older than that, you’ll have some brick cracking and replacing,” says Isles.

Despite the long winters, plenty of New England communities love a good outdoor pool. Ignoring a pool system will wear it down quickly. Not cleaning the pool regularly and having too much chlorine in the water will damage the pool; daily management techniques should be known by building staff, who can be taught them by vendors if needed. And while it might seem like not much harm could be done from improper care for a pool, consider that a complete system overhaul for a pool could cost a bundle. On the low end, it might cost a building as little as $5,000, or as much as $100,000, depending upon the pool’s size. “Typically, you have a service contract with a pool maintenance company and they keep an eye on the equipment. A lot of times if you go for a cheaper piece of equipment, you end up paying for it to be maintained. The more expensive filters and pumps, those require less maintenance dollars. Do you spend the money on maintaining it, or on a higher quality piece of equipment?” says Allen.

Proper maintenance is the most important of all the factors that can extend the life span of any building system. Other factors such as foot traffic may not be able to be controlled, nor of course, can the weather. So make sure your building staff takes care of what it can.

Scheduling Upgrades

A building’s administrators should collaborate with their service pros to determine whether it’s better to repair a failing system or replace it. Saving money for residents is part of the job of a board, and that’s where capital reserve studies come in. As part of capital reserve studies, major systems in the building are evaluated to determine how much usable life they have. This is done through a visual inspection of the building, by professionals referring to manufacturer’s specifications on the system, and through an evaluation of info on problems and repairs done to the systems.

Also for a reserve study, maintenance professionals who service the building will be consulted to evaluate the longevity of the system and to help give recommendations. While there are clear industry standards, weather and climate has to be taken into account. “The importance of reserve studies, is they might not just pick a number out of the guideline tables. You actually take a look at the equipment and the condition of it and the environment that it’s in,” says Carr. “If you’re in an area that’s near the ocean, you’re going to have a tremendous amount of corrosion in the condensers and the external units, and their life spans can be reduced by as much as 60 percent. We see that along the coast of New England. Exterior units get replaced a lot more often, than say, the countryside,” he says.

The frequency with which a building conducts capital reserve studies varies from community to community and is partly dependent upon the size and type of community. These studies are usually done by an engineering firm or another firm which specializes in such work. Experts recommend doing a capital reserve study of a co-op community every 5 to 10 years and doing a reserve study every 5 years for a condo community.

Thanks to Moore’s Law—which says that that processor speeds, or overall processing power for computers will double every two years — and the speed of change in the computer era, some electrical systems such as security systems and entry systems may need to be replaced more frequently than other building systems. And some residents want greater security or more convenience, so changes to the system are made to make things easier, such as by upgrading to a keyless entry. And due to technology constantly morphing, a building’s computer network might have a life span of only 15 or 20 years.

Jonathan Barnes is a freelance writer and regular contributor to New England Condominium. Editorial Assistant Tom Lisi contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment