It was January 1977 when the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) first identified and isolated a previously unknown strain of bacteria found breeding in the cooling tower of a hotel air conditioning system. The bacteria, subsequently named Legionella, caused an outbreak of what is known as Legionnaires Disease, and the world first became aware of the concept of ‘sick building syndrome.’

Thirty-four people died from that particular 1977 outbreak, and an additional 200 people required treatment. A new industry sprang up worldwide to identify, isolate and remove the cause of when a home, office or building is diagnosed with Sick Building Syndrome or Building-Related Illness (BRI). And it’s not going away. New York City just suffered through such an outbreak due to infected cooling towers, in which 12 people have died and over 100 were sickened.

Obtaining a True Diagnosis

It’s important to realize that Sick Building Syndrome is not a specific disease; it’s a constellation of several clinically recognizable features when symptoms appear in a significant number of people occupying a particular building. The term is used to describe situations in which building occupants experience acute health and comfort effects that appear linked to their time spent in the building, but no specific illness or cause can be identified. BRI is the term used by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) when symptoms of a diagnosable illness are identified and can be attributed directly to airborne building contaminants. Using these criteria, the Legionnaires Disease outbreak in '77 was actually a Building Related Illness, and not Sick Building Syndrome.

Laureen Burton, a chemical toxicologist with the EPA in Washington D.C., helps explain the difference between SBS and BRI. “In general, BRI symptoms are easier to define clinically than SBS, and appear linked to the time spent in a building. The illness can often be identified as directly attributed to building contaminants.” Burton points out the most common factors contributing to indoor environmental quality (IEQ) are not new. “Most IEQ problems result from inadequate ventilation, temperature, humidity and even lighting problems.”

Chemical contaminants from indoor sources pose additional problems when there is misuse, improper installation, or just poor maintenance of products and appliances. Excess moisture indoors is a problem in itself, and when combined with other factors, it may complicate a speedy resolution.

Lance Eisen, chief of operations with the National Organization of Remediators and Mold Inspectors (NORMI), notes weather, climate, and even local economic conditions can have an impact on conditions in a building. “Some of the conditions contributing to SBS are temperature, humidity, particulate, chemical, biological, radiological, comfort, and electromagnetic,” he states. “Also any combination is possible.”

He points to changes in construction with a focus on energy conservation, and the usage of more artificial materials as additional factor on indoor air quality. “Artificial materials can give off gas for years, releasing chemicals into the breathable environment. This in conjunction with a tighter structure can cause extensive exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOC).”

Older Construction vs. New

Burton and Eisen agree that old construction is no safer against SBS than new construction, and any structure can become a sick building. “The good news is most buildings can be made healthier, which in turn can prevent SBS,” says Eisen. So what are the symptoms of a sick building and what steps should you take if you suspect your property may have a problem?

“The most common tell-tale that there is a problem in the building is a sense of not feeling well when spending time in the building. Odors, rashes, headaches, stress, mood changes, and many other physical or physiologic symptoms can occur or be detected,” says Eisen. Burton recommends occupants of a building note their health-related symptoms or discomforts and see if they get better when spending time away from the building. “Complaints in buildings may be localized in a particular room or zone, or may be widespread throughout the building,” she states. If symptoms improve when spending time away, Burton cautions there may well be an indoor air quality (IAQ) problem in the building.

Steve Dumas of Florida-based Rainbow International Restoration works with sick buildings (as well as damages and cleanup from fire, smoke, and water), and says he is no stranger to SBS. His rule of thumb is if 20% of a building’s occupants complain of various symptoms (primarily in air conditioned facilities) that go away upon leaving the building, chances are that the building itself is ‘sick’. Most typical symptoms include but aren’t limited to, flu-like symptoms, fever, lethargy, fibromyalgia, and allergies.

When checking indoor air quality, Dumas looks at seven components to determine if there is a problem and if so where the problem lies: temperature, comfort, humidity, odors, particles, bio-pollutants, and gases emitted by cleaners are all possible sources for SBS. “If the symptoms persist over time, the human body tends to react in one of three ways: allergic response, disease response, or toxic response,” he explains.

Other common building health-related problems include eye irritations, nasal irritation, throat and lower respiratory tract symptoms, dry throat and/or difficulty breathing. Headaches and fatigue, skin problems, including eczema and dermatitis are also frequent complaints relating to SBS.

Eisen feels it is often difficult to qualify both problems and symptoms. He agrees that any of the above ailments or a combination thereof coupled with an individual’s immune system, current health, family history, and age can increase—or decrease—the effects of SBS. And he raises another interesting point: “Sick Building Syndrome may present no symptoms at all, but compromise a person’s immune system and cause other health issues to become worse.”

Preventative Measures

Cleanliness and routine maintenance are two excellent starting points for keeping a property healthy. While performing regular activities, it is easy for staff and maintenance crew to notice areas of possible concern. Is there a leak or standing water? Do filters need replacing? Is ventilation adequate, and humidity controlled?

These very basic questions are where a professional will probably start when called to inspect a building. Burton outlines the process. “Depending on the situation and investigator, inspections can vary. In general, the process includes an initial walk-through and visual inspection of critical building areas and consultations with building occupants,” she says.

This initial process is a gathering time used to assemble information about the history of the building, basic operation and maintenance procedures, and the complaints. “This information may allow the investigator to develop possible explanations for the complaints or concerns. The rest of the inspection and investigation process will depend on the outcome and findings of these initial steps.”

Eisen mentions the many hours of training required when formulating an approach for a specific building. Like Burton, he expects visual assessments, and interviewing occupants to be part of the process along with compiling common or targeted areas of concern. The experience of the specialist will come into play at all times during the procedures.

At some point, gathering air samples for lab analysis may be suggested by residents or board members, but this is not an exact science and cannot guarantee a solution. “Sampling can be done by most people with the correct equipment and training,” says Eisen. But he goes on to explain analysis of the samples must be performed in a lab by a trained microbiologist, and understanding those results and how they affect a building and the occupants is an entirely different story.

Burton agrees adding, “Except in cases of radon, it is generally not recommended to do air sampling for contaminates indoors because they are often costly, in most cases there is no uniformly accepted standard or threshold for comparison in residential settings. The information provided often will not help identify the cause of the problem and can even be misleading.” She suggests using simple basic measurements such as temperature, relative humidity, CO2 and air movement instead of sampling to provide a “snapshot” of current building conditions.

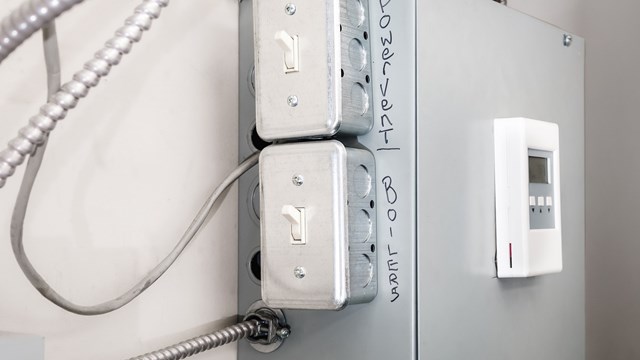

Duct cleaning may not be a quick fix and easy answer to concerns either. Eisen recommends routine annual and seasonal HVAC inspections with regular filter changes. “Filters should be changed based on the particulate load in an area, the population of the building, and any SBS-related issues.” Burton also takes a conservative view of duct cleaning, “Much of the dirt that may accumulate inside air ducts adheres to duct surfaces and does not necessarily enter the living space. The EPA only recommends air duct cleaning on an as-needed basis.”

Exceptions to that recommendation would be if ducts are clogged or infested with vermin (rodents or insects being the most common) or if there is visible mold growth on any component of the heating and cooling system. Dumas echoes the other professionals: “Have a licensed HVAC contractor regularly inspect the system, and change the filters.” He recommends what he calls thoughtful remodeling. And, make sure you “control moisture problems with proper construction, and the use of landscaping, gutters, attic and crawl space ventilation, and routine maintenance.”

Clean and Green

“Thoughtful remodeling” is an idea that can extend to careful consideration of replacement flooring. Hard surface instead of carpets may reduce chemicals in the environment, and Burton suggests carpet never be used in areas where moisture is a problem (water fountains, sinks, etc.) Burton provides a short list of easy “can do” suggestions including steps to reduce indoor humidity with adequate venting and dehumidifiers, using exhaust fans, and immediately cleaning wet areas to prevent mold growth.

Using “green” products in the correct amounts and correct way is also a proactive way to improve overall air quality. The movement toward more environmentally healthy, “green” products and practices has helped focus attention and awareness on sick building syndrome and building-related illness, and ways to avoid both. It is not surprising that products and materials that are better for the environment are usually better for people, too.

SBS and BRI can be caused by several underlying factors. Many residential buildings are taking steps to make their interior environments healthier, with help from local, state, and even national organizations offering incentives and support programs. If you suspect your building may have SBS or even BRI-related issues, Burton recommends contacting local governmental offices. “Local governments will know which resources are available for your location and state,” she states.

Anne Childers is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment