The era in which too many condominium boards shrugged off warnings about inadequate reserve funds or postponed needed maintenance has come to an unsettling end.

In a series of recent high-profile episodes, condominiums have been hit with staggering assessments, suffered bitter political infighting, or even been forced to evacuate owners when faced with sudden or overwhelming maintenance needs.

To make things worse, the aging nature of the condominium stock in New England has engineers predicting that many more condominiums will face similar severe difficulties in the not-too-distant future.

Three recent cases highlight the severity and extent of the problem.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, Longhill Gardens Condominium nowsits entirely empty after city inspectors condemned successive blocks of units for health and safety violations. While the community was becoming uninhabitable, vital business records disappeared, heating oil tanks were left empty, and a no-holds-barred legal fracas erupted between a group of investor/owners and the majority owner, who last year was jailed on contempt of court charges.

In Miami's trendy South Beach District, Castle Beach Condominium owners were forced from their upscale units for 2 1/2 years while a host of electrical and structural problems werefixed. The owners only started trickling back into their units earlier this year, still smarting from paying both assessments and monthly condo fees on units they were unable to use—in addition to temporary housing costs.

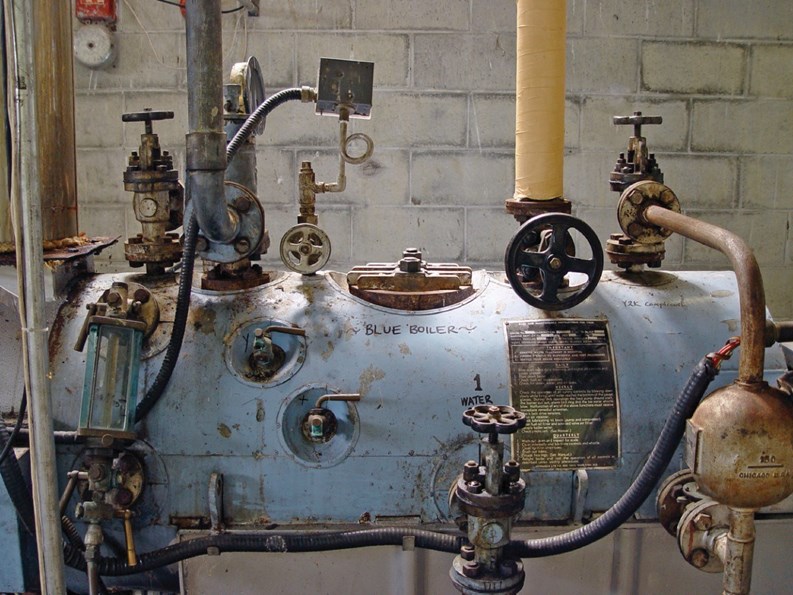

And in Boston, Harbor Towers Condominiums was hit with a $75.6 million special assessment—believed to be the highest ever in Boston—to cover costs of repairing and replacing the heating and cooling systems of the two waterfront mid-rises. The one-time assessment, ranging from $70,000 to $400,000 per unit owner, led to a bitter political struggle and assertions by some residents that they would have to sell their units to pay the hugebill, due November 29th last year.

Fortunately for Harbor Towers, the situation has eased, and over 95 percent of the assessment had been collected asof late January, according to a letter from its trustees.

Condos Ill Prepared

While Harbor Towers has pulled through its ordeal, many other communities are in no position to deal withsuch a challenge, says engineer Ralph Noblin, of Noblin & Associates, LC, Consulting Engineers in Bridgewater, Massachusetts.

"There are people at Harbor Towers, some well-heeled stockbrokers, who could probably write a check for $400,000 or whatever. But there are some people in Dracut, in Gardner orGrafton who would be hard-pressed today to write a check for $1,000," notes Noblin, who didn't work on the Harbor Towers project but has advised condominiums for decades on difficult engineering issues.

"Condominiums have been kiddingthemselves for, in some cases, 20 to 25 years, what it really costs to live in a properly-run condominium," says Noblin.

The start of under-funding reserves at many condos, says Noblin, dates back to the mid-1980s' building boom, when many condo fees were set at around $100 a month, with only$8 to $10 a month going toward repairs. "In the course of a year, that's only $100 a year, per home going into reserves," says Noblin, who adds, "The real numbers should have been close to $1,000 per year, per home."

Noblin says he and other engineers started telling boards in the late '80s and early '90s that their numbers were way too low, but "people looked at us like we had two heads." Even if some board members did believe him, Noblin says inaction was frequently chosen "because most of their [capital improvement] projects were [years] down the road."

"When values are going up, people are more amenable to spending money on their homes, thinking, "My home's worth $400,000 now. They're looking for a $40,000 special assessment. I think my home will be worth $450,000,$475,000 in a couple of years, I'll get that money back," he says. "Now you don't have that dynamic. You have the dynamic where, 'My house was worth $400,000, now it's only worth $280,000, if I can sell it, and they want a $40,000 special assessment?' You can make the argument that your home is worth only $240,000."

With homes losing value, Noblin says the easy-to-get home equity loans that have provided a cushion against unexpected assessments are no longer available.

Further aggravating the problem, says Fernandes, is that while real estate values have flattened, the price of construction materials has skyrocketed. "Roofs, vinyl siding, virtually every construction component has escalateddramatically. At the same time, you have people not wanting to put as much money away."

Up In Arms

The result of the two trends converging is significant political conflict, splitting communities and spawning lawsuits and insurgent move-mentsaimed at boards of directors who pursue expensive repairs.

"I've been to meetings where no one in the room would accept or acknowledgewhat really needed to be done. They were in denial, they were in tough financial straits," says Noblin. "They were, 'Who do we blame here?' and 'Who stole the money?' These meetings, unfortunately, are going to get worse and get greater in numbers," he says.

Owners who form opposition groups and commission engineering studies they hope will disprove the need or scope of repairs are mostly misguided and a little ironic, says Noblin. "They're screaming at the outset that they don't have the money to do the project, yet they're willing to spend money for a second opinion that really isn't necessary."

At Harbor Towers, the news of the $75.6 million assessment tore the close-knit community apart. A unit owner/ engineer challenged the engineering report, called for a more modest fix and filed a suit against the trustees for breach of fiduciary duty. Pro- and anti-repair slates of candidates clashedin a bitterly-fought election while a petition circulated demanding that any ongoing work be halted.

The turmoil over the assessment has finally calmed down this year, says investor unit owner William Packard, who works for Coldwell Banker in downtown Boston. Unit sales that were on hold because of uncertainty over the assessment are now moving ahead, a construction trailer is on-site, and a dramatic helicopter airlift of mechanical equipment onto the roof of Tower One recently took place, he says. "There is a green light and they are progressing with the work right now," says Packard. "It's a reality that everyone has accepted."

Condition Assessment

To prevent a situation like Harbor Towers from developing at other condominiums, Fernandes recommends that reserve studies be regularly updated, and a "building condition assessment" be done, particularly at mid- and high-rise buildings.

"A reserve fund is for those planned cyclical replacements but sometimes—especiallyin the larger buildings—you can have façade issues or water infiltration that causes damage that isn't anticipated," says Fernandes.

To guard against unanticipated damage, many condominiums hire Fernandes' firm to fly over their flat roofs annually and do infrared roof scans to spot leaks not yet visible. "[We] look for the beginnings of problems before they escalate out of control," he says.

Whether it's putting aside enough reserves, updating reserve studies or even doing building condition assessments, Fernandes says boards have a legal and moral obligation to their communities.

He has little sympathy for board members who short reserves or postpone work, figuring they'll be gone when the bills come due.

"It's extremely short-sided and unfair. The whole idea of the reserve study is a pay-as-you-go philosophy. You're not paying for a future roof, you're paying for the roof that's over your head right now. If it's a 20-year roof, your putting away 1/20 of the value each year and basically each homeowner is paying for that roof as they use it up. The idea is when the roof is used up, the money will be available to replace it, rather than just try to put off to some future unit owner to pay for," says Fernandes.

"So the board members all have that fiduciary responsibility, not just to the current homeowners but to future [owners] as well."

Leave a Comment