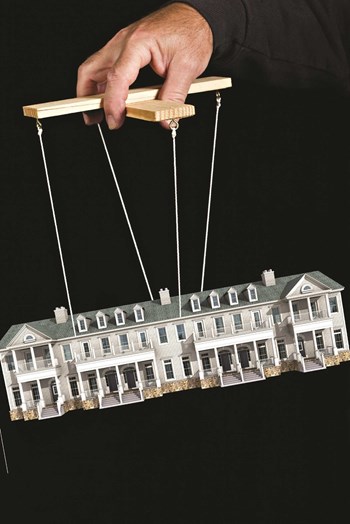

The goal of any property developer is to sell units, but until that objective is reached they have to assume all the day-to-day responsibilities to ensure smooth operations and continued sales. This requires wearing many hats—manager, board member and ombudsmen. As a result, it’s often a a relief when control of the property is transitioned to members of the association. However, this isn’t always the smoothest of processes, and developers and unit owners can quickly become enemies, if a clear and effective transition doesn’t take place.

In Massachusetts, there’s not a very a clear legal framework for transitions, which lead to confusion in the process.

”In Massachusetts, it’s all set forth in the master deed, sometimes it’s in the declaration of trust. Somewhere in the documents, there will be a paragraph about the trigger for turnover,” says Diane Rubin, partner at the law firm Prince Lobel in Boston. “If you’re buying in a brand-new building, when 75% of the units have been sold, or two years from the day of the recording of the master deed is usually when the transition happens. I’ve seen some developers and their lawyers put in the documents that the turnover date will be in seven years, which is past the statute of repose for construction claims. It’s arguably against public policy, but it’s an open issue in Massachusetts,” says Rubin.

Obviously the idea of a board of trustees in the first place is to make sure at least a few people are legally responsible for keeping the best interests of the community. Just like owner-run boards, the developer has a fiduciary duty to act in those interests when it runs the board. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always happen. “Even if it’s just for a year or two, the first board that controlled by the developer, the interests of them are very different than the issues of the unit-owner board. If you have to spend $50,000 to repair something that isn’t working right. Does it get paid for by the developers or the unit owners?” says Rubin.

“The developers want to wear as many hats as they can, so they think they have all the power. They want to be the developer, the trustee and the manager. That sets up not only an inherent conflict, but sometimes an inherent problem when you get to transition. If you’re all those three things, and the association doesn’t have all the records in place or the payments have been made in a manner that the shouldn’t, you’ve already created a trail that leads right back to you for a case of negligence,” says Charles Perkins, senior partner at Perkins & Anctil in Westford, Massachusetts.

A Managed Transition

While it’s commonplace for developers to hire management companies to oversee the building or property prior to transition, there are often related issues that can impact the unit owners and board members once the baton is passed. “If it’s a bigger building, the property managers will help organize the transition, as far as setting up elections and meetings, and do the distribution and hold the election. There’s a due diligence process that the board can take. Sometimes a more sophisticated board prior to turnover, will have an advisory group that will work with the developer prior to that turnover election, to spend some time looking at the books and records together, and looking at outstanding issues with parking or noise issues, etc.,” says Rubin.

The old adage of too many chefs in the kitchen can come into play after transition, especially when a developer still has influence on the board. As a result, certain challenges can be presented. “Assuming that there are no physical or fiscal problems with the condominium, the board really has a few other things that they should do. Based upon their size, they should determine the type of management that they’re going to have, and the other professionals that are going to be needed,” says Henry Goodman, an attorney and principal with the law firm of Goodman, Sharpiro & Lombardi LLC in Dedham, Massachusetts. “The fact of the matter is, a two- or three-unit condominium probably doesn’t need anything professional except an accountant. Every association has to file a tax return. On occasion they need a lawyer to review their documents to make sure they’re not outdated or have gaps. Often people who draft documents copy documents that were drafted years ago. Laws have changed, and conditions on the ground have changed. Thirty years ago people used to put in overbroad insurance language, and did not provide for deductibles because insurance premiums were cheap and you could a $500 deductible. Nowadays a deductible can be over $20,000 and premiums are in the tens of thousands of dollars. You have to make sure you have modern language that will protect the associations,” says Goodman.

Of course, many buildings do have physical issues in the first few years, and major building issues so early often leads to the construction effort. This can be a major sticking point for both the unit owners and the developers. “Most developers are not going to give you money as a transition committee to investigate what they did during construction. If you’re building 200 units, and the first year, there’s nothing to investigate necessarily the first year. If unit owners are meeting and already running into problems like cracked roofs, then you might want to get involved and take matters into your own hands, but that can get expensive. There are developers that form transition committees themselves, put unit owners on them, and work very transparently on an ongoing basis,” says Perkins.

Of course, not all developers will try to take advantage of their power like this. Even aside from the lack of ethics, some developers seek to make the transition process as painless as possible for all involved. It’s not unheard of for developers and unit owners to temporarily share power on the board. And while some will try to hold on to their control of the board for as long as possible, others also just went to get in and out, and will be the initiators to kickstart the transition. “Lots of times, the developer will be the first to bring up the transition, because they’re happy not to have to do it anymore. A lot of times, a property manager will do it because they’re aware of the need to have a transition, and also unit owners will do it,” says Rubin.

“A new board has to come into office in accordance with whatever provisions the condo documents are. Usually it’s by election. As soon as the election has been held, and independent board members are elected, someone has to draft a certificate of election and get it recorded at the registry of deeds. Not all documents but most require that the certificate be recorded before the trustees officially take office,” says Godman. “The new board has a duty to investigate the physical plant, to determine whether there are any endemic problems that need to be addressed by the developer, and they also have to examine the fiscal plant, by having an audit done of their books and records by an independent CPA, to make certain that there was no financial wrongdoing, such as burying construction costs in association fees, lowballing the common fees, things like that.”

Since being proactive and informed is the best policy for a property that is expecting transition, it’s ideal when prospective board members do their due diligence. The reason is that developers are also in the process of closing a long-standing project and are often overloaded. “I often have clients contact me and they say something like this: ‘Our developer wants to give up control. Should we accept it before he takes care of problems that we know exist?’ That’s evidence of a total lack of understanding. An association exists as of the first day that the condominium exists. It’s just that the board is composed of appointees by the developer. Eventually the developer turns over the board,” says Goodman. “The longer you wait, the more likely it is that the statute of limitations runs out with regard to those problems, and the developer will no obligation to fix them at all. By taking over the association, you now have control and can bring the developer to task.”

Elections and Governance

Even when a new board has majority control of the property, they must formulate policies in conjunction with laws on the voting and the management of the collective, which could include dealing with one or more developer appointed members. The majority of an association’s rules and covenants are in place long before a single unit owner has purchased their home. This is stated in the declaration of condominium, bylaws, articles and rules and regulations filed by the developer on behalf of the association. Regardless if a developer remains involved after turnover of majority control, most new boards, concern themselves with specific adjustments to the rules that are raised by events that occur on the property. The good news for boards is that after transition, despite the possibility of the developer presence, the board holds the majority vote to make decisions that will best serve the community. It is at this stage that the board should build its roster of professionals to ensure that no snafus are realized.

All board members should use available industry information that will better assist them in their respective roles. “The best thing to do is to be educated. CAI has a number of different courses that can train people who want to become board members. They should really think of trying to attend those, because they give you a lot of knowledge from people who are in the industry,” says Perkins.

W.B. King is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium. Editorial Assistant Tom Lisi contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment