There are certain perils—fires, major weather events, and so forth—that announce themselves clearly; others are more subtle, if no less hazardous. Things like gas leaks, electrical shorts and surges, and water leaks may not be as dramatic as a hurricane or a nor’easter, but the damage they can cause can be staggeringly expensive. Let’s look at how residents, managers and building staff can recognize the signs of these utility-related hazards, and what they should do when they encounter them.

Gas Leaks

Recognizing a natural gas leak is simple—if you hear a hissing sound and smell rotten eggs, or just notice the smell, there’s probably a leak. When natural gas is first extracted from the ground it is clear and odorless, but due to its explosive tendencies a chemical called Mercaptan is added to it before it’s sent out to people’s homes to give it the distinct rotten egg smell as a safety precaution.

“If you have a gas leak one of the first things is leaving the area immediately,” says Judy Comoletti, division manager of public education at the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). “Get out of the area and to a safe location. If you’re in a multifamily home you should notify all of the other residents and the authorities right away.”

When mixed with the air, natural gas can be ignited with a simple spark—even a static shock could do it—so leaving the area, warning building management as well as neighbors and contacting the local fire department should be the first priority. Beyond that, "Don't light a match or smoke, turn appliances (including flashlights) on or off, use a telephone or start a car," advises National Grid, an international electricity and gas company that operates across the U.S.

The most important thing to do is to call the local fire department immediately—and then follow their directions. All fire prevention pros stress the importance of calling 911 or your local utility if you suspect that you smell gas—don't ever assume that someone else will call. For everyone’s protection, leave the area and make that call yourself.

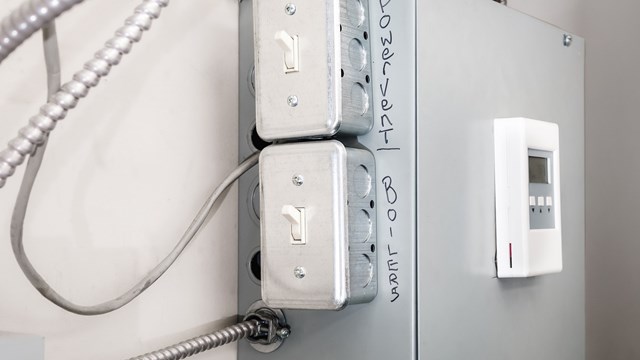

Electrical Shorts & Surges

Not quite as devastating as gas leaks, but still fraught with potential danger, are electrical shorts and surges. An electrical fire can rip through a condo, or an entire building, in no time, and are among the more difficult fires to put out.

“Never attempt to modify or adjust electricity, utilities or large appliances yourself,” advises one safety pro. “Always consult building management beforehand, and only utilize a licensed professional.”

“In Massachusetts, fire officials recommend having a licensed electrician review your home’s electrical system every ten years,” says Jennifer Mieth, a public information officer with the Massachusetts Department of Fire Services. “Small upgrades and simple safety checks can prevent larger problems.”

Remodeling is a good time for a complete inspection of your electrical wiring. You want to make sure you know the warning signs if you’re having issues, like if you’re blowing fuses or tripping circuits, you should get a qualified electrician.

“While it is permissible for homeowners to do their own electrical work in our state, we strongly recommend hiring a licensed professional,” Mieth says. “They will know the code which is updated all the time. They will know when to get a permit for the work and then the homeowner is protected by the electrical inspector making sure it was done correctly. Personally, living in a house where the former owner did a lot of things himself, it is very scary.”

The experts spoken to for this article all recommend using products and appliances endorsed by Underwriters Laboratory, one of several companies approved to perform safety testing by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). That means the plugs and switches bearing the “UL” insignia. By doing this you can ensure that your plugs and switches have been thoroughly tested and vetted.

Another pro tip: ditch the extension cords. Fine for alarm clocks and the occasional lamp, but they should be used sparingly, and avoided outright if possible. Plugging directly into a wall socket is always preferable. “Extension cords are designed for temporary use, not permanent use,” Mieth explains. “Avoid using extension cords, especially with heat-generating appliances like space heaters. Such appliances should be plugged directly into an outlet. If you must use one, make sure it matches the wattage of the appliance and both are rated by an independent testing lab such as UL. Often when we have space heater fires, they are actually overloaded extension cord fires.”

Water Leaks

Water operates more slowly than fire, but is potentially even more devastating. Remember, it’s water, not fire, that over the course of time can bore holes in the mountain ranges where rivers flow. Leaks in multifamily buildings can erode masonry, rot wood, crumble drywall, and corrode metal. It can also cause mold to proliferate, which has been linked to an unpleasant array of health issues for residents.

Happily, water leaks tend to reveal themselves quickly, and damage is often mitigated by turning off the local water supply until repair can take place. Unhappily, water leaks tend to rain into the apartments below their source, which can have a deleterious effect on neighbor relations. If the telltale signs of a leak—damp spots, staining, softening or sagging drywall, and obviously actively dripping water—show up in an apartment or common area, it's crucial that the situation be reported to management or building maintenance staff immediately. The faster the source of the leak is identified and neutralized, the less chance there is for long-term or serious damage.

Carbon Monoxide

According to National Grid, “Carbon monoxide (CO) is an invisible, odorless gas that can be deadly if left undetected. When fuels such as natural gas, butane, propane, wood, coal, heating oil, kerosene, and gasoline don’t burn completely, they can release carbon monoxide into the air. Common sources of carbon monoxide include malfunctioning forced-air furnaces, kerosene space heaters, natural gas ranges, wood stoves, fireplaces, and motor vehicle engines.” Cooler months are an especially perilous time for CO leaks. “During the heating season, windows and doors tend to remain tightly shut, sealing out fresh air. This creates the potential for carbon monoxide to build up over time.”

Carbon monoxide poisoning can kill you—but even in smaller doses, it can make you really sick. The symptoms of CO exposure, National Grid explains, are akin to the flu, and include “headaches, weakness, confusion, chest tightness, skin redness, dizziness, nausea, sleepiness, fluttering of the heart or loss of muscle control.”

“It’s called the invisible killer since it can’t be seen or smelled,” says Comoletti. “We’re seeing so many instances of carbon monoxide poisoning. The winter months are the leading times for the issue. It’s important to have your furnace and central heating cleaned every year. If electricity goes off and you need to use a personal power generator, it must be outside the home, in a well-ventilated area. If you start a car it should be out of the garage. Make sure the tailpipe isn’t obstructed by anything; same with vents going out of the building.”

If you do not have them already, high-quality CO and smoke detectors are a must. In fact, Carbon monoxide (CO) alarms have been required in nearly every residence in Massachusetts since March of 2006. In 2014, Massachusetts fire departments responded to just over 15,000 CO incidents—and in one-quarter of them, or over 4,000 cases, the presence of carbon monoxide was confirmed. “Functioning smoke and carbon-monoxide alarms save lives,” says one expert. “Test your home’s smoke and carbon-monoxide alarms to ensure they are working, and review the household fire safety plan with anyone who will be living with you.”

“Generally, CO alarms need to be placed on every level of the home and within 10 feet of every bedroom. Since CO mixes with air, they do not necessarily need to be placed on the ceiling. That‘s why there are plug-in models,” Mieth says. “But they do need to be replaced every five to seven years unless they have a sealed 10-year lithium battery, newly on the market.”

“If the alarm sounds you should get to a fresh air location, either outside or by an open window, and call the fire department,” adds Comoletti, “People need carbon monoxide alarms in their homes.”

These sort of perils can involve everyone who lives in the building complex. Whether an extreme situation, like a gas main explosion, or a more controlled one, like a leaky sink raining into the unit below, residents of co-ops condos and HOAs share in the dangers. It is part and parcel of living in residential housing to be vigilant—for you, your family, and your neighbors.

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium. Staff writer John Zurz contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment