Property management, in the broadest of terms, is defined as the operation, control and oversight of real estate. Most property managers would agree that this particular definition is just a starting point.

There are many facets to the demanding profession of property management, including managing the accounts and finances of the real estate properties, and participating in or initiating litigation with tenants, contractors, vendors and insurance agencies. Litigation may be considered a separate function, set aside for trained attorneys, but a property manager will need to be well informed and up to date on applicable municipal, county, state and federal Fair Housing laws and practices.

Remember to Communicate

One major role of a property manager for condominium properties is that of liaison between the board of trustees or the board of directors, the property owners/residents, and the personnel required to keep a property attractive, safe and functional. Good communication is a must for this “thinking-on-your-feet” position which also requires understanding the processes and systems utilized to manage all aspects concerning property including acquisition, control, accountability, responsibility, maintenance, utilization and disposition.

“A successful property manager is basically a jack of all trades,” says Lynne A. Kelly, CMCA, MCL, CPO of Kelly Property Management Corporation in Burlington, Massachusetts. “Property managers know a little bit about everything; that way they have the ability to help associations run smoothly.”

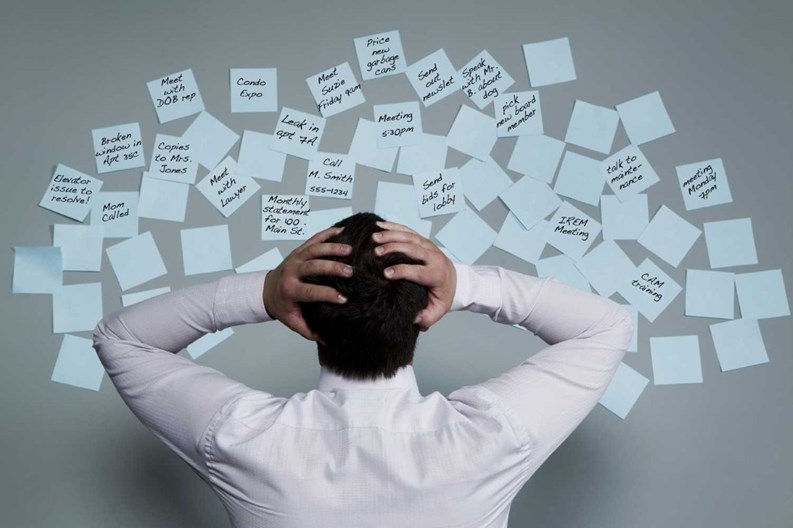

“I think it’s important for a property manager to have patience, organizational skills and follow-up,” says Melanie DeMaria, CMCA, a property manager with Crowinshield Management Corporation in Peabody, Massachusetts. “Patience is important because you deal with a lot of different personalities with the board of trustees and the homeowners. Organization is important because you are always multi-tasking and if you don’t stay organized it just kind of tornadoes.”

Michael R. Phillips, chief operating officer of the Copley Group in Boston, agrees with DeMaria on the importance of organizational skills for property managers. “It’s extremely important for property managers to be organized and focused,” he says. “The ability to multi-task is important too, as is having a thick skin, being political but most of all being proactive.”

In the Beginning

Property management as we know it today is a relatively new profession. As the feudal system of land ownership in Europe gave way to the industrial revolution, the beginnings of the real estate business we know today began to emerge. By the middle of the eighteenth century, land ownership in Europe and in England particularly, assumed a different significance. As cities grew, land and buildings became a favored means of investing, and it wasn’t long before America’s shores and emerging industrial cities encouraged investors to cross the Atlantic.

Initially buying, settling and reselling land masses in this country was stimulated by increased population and immigration along with the European market demands for more and newer products. As the industrial age spurred tremendous growth, America’s newly formed cities, stores, offices and rental properties increased to meet the needs of a thriving labor-driven economy. America was a goldmine for property investors, and the real estate industry we know today began to take shape. Property management was not far behind.

John Jacob Astor was already a millionaire from fortunes amassed in fur trading when he turned his interest to real estate in the middle 1800s. His motto concerning land and real estate was “buy and hold, and let others improve.”

That mindset was shared by many investors, who purchased land and property and hired others to manage and maintain those investments. This new class of wealthy Americans sought assistance in the management of their real estate assets as multi-apartment buildings and a high rental boom ushered in the new century.

During the Great Depression (1929-1939) financial institutions recognized the experience and knowledge of property investors and managers, and relied on the combined expertise to help bring about stability in the marketplace. After the Depression, the size and scope of property management developed rapidly to become the well-defined professional arm of real estate we rely on today.

The Day-to-Day Hassles

There are many avenues into the field of property management. A bachelor's or master's degree in residential property management at a traditional university, or online degrees in real estate management are readily available for those interested.

New England property managers can also turn to several active chapters of top-tier professional organizations including IREM’s Boston, Connecticut and Rhode Island chapters, and CAI’s New England, New Hampshire and Connecticut chapters, to find opportunities for continuing education and certification. Some of the professional designations awarded to property managers include IREM’s Certified Property Manager (CPM) and Accredited Residential Manager (ARM), and CAI’s Professional Community Association Manager (PCAM), Association Management Specialist (AMS), Large Scale Manager (LSM) and Certified Manager of Community Associations (CMCA).

Regardless of the training, there are character and professional traits all successful property managers share, starting with time management, and a background in business and financial administration also translates well to this multi-faceted profession.

Picking up checks, reviewing projects, and working with vendors are all in a day’s work for a property manager.

“My typical day is returning calls and answering emails that I usually do on my phone on the way into the office,” says Kelly. “I’m calling vendors, trying to deal with complaints and trying to arrange appointments for various jobs being done around the association. A lot of property managers will have set times but we feel in our company it’s better to try to take care of the issues as they arise. I try to make sure I give quick customer service to our associations.”

“There are always several things going on at once and we tackle them as they come, but we also prioritize them,” says DeMaria. “Every week we’re assigned to go to our properties for site visits. I like to go the first thing in the morning. But on an average day I’m usually in the office first thing in the morning checking emails, following up with vendors and trustees or I’m on-site meeting a contractor.”

Kelly recalled a recent incident when a unit owner called her in the middle of the night complaining that there was a bird’s nest in a light above a doorway. “I told them that we will not, under any circumstances, remove a bird’s nest if there are eggs in it in the spring. Another example of emergencies that are not emergencies is in the winter time during snow season. I’ve gotten calls at two o’clock in the morning because there’s snow blowing and they don’t want snow blowing to happen until later—but when you get 18 inches of snow you have to stay in front of it.”

“I think every day is not an average day in the property management business,” says Kelly. “There’s always an association member or unit owner or trustee that thinks something is an emergency and it’s really not.”

“My average day consists of visits to the sites, telephone calls and emails with vendors, contractors, unit owners and communicating with boards,” adds Phillips. “A not-so-average day would be an emergency of some sort like water is leaking from a bathroom on the fourth floor and it is impacting all units below it. Everything stops when we deal with an emergency, and we have to keep the board informed of what’s going on.”

Working Together

The responsibilities of property managers include a wide range of duties, from the physical to the administrative—but one of the most important is working alongside board members to provide a harmonious environment for all residents. Property managers interviewed for this article agree that they function best when boards are decisive and give clear direction.

“It is extremely important for property managers and boards to work together,” says Kelly. “It is true that property managers work for boards and associations, but you have to work together in order to get things accomplished. I feel for the most part, most managers have a better understanding of how things work, whether it be a project or knowledge of vendors. It’s important to take recommendations from property management companies because they have the knowledge that comes from working with lots of vendors and they may also be a homeowner or unit owner.”

“I wish boards and HOA residents knew the effort that we put in and that we don’t manage just one condominium,” says DeMaria. “A portfolio manager has several different sites and in one day we try to tackle all of the problems in all of them and not just one.”

“It’s important for boards realize that a property manager’s primary job is to manage the property,” says Phillips. “Too often boards think that any task at hand is the responsibility of the property manager. A few examples are creating a unit owner handbook, dealing with legal issues or dealing with an individual unit owner that is a hoarder.”

A tough job can be made a whole lot easier when you love what you do, and most successful property managers usually love their jobs. And even a superhero can attest that helping people can invariably make a positive difference in the world around them.

Anne Childers is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium. Staff writer Christy Smith-Sloman contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment