If you think about it, a multifamily building isn’t that much different than the human body. Both house important complex operating systems and organ-like pieces of vital equipment; both take in fuel and produce waste; and both require regular check-ups and a good maintenance program to stay healthy and thriving.

And just like humans need to see doctors regularly for updates on the heart, lungs and eyes, buildings need to have examinations of their systems as well, with checkups required for HVAC/chillers, plumbing, electricity, and the building envelope.

Charles A. Merritt, PE, president of New York-based Merritt Engineering Consultants, P.C., notes a multifamily building’s primary operating systems include the building envelope, waterproofing, electrical, mechanical, plumbing, and elevator systems, as well as heating, ventilation and air conditioning, or HVAC. “Each of the building systems can present a number of problems that will affect the level of comfort in the building,” Merritt says. “One notable problem that can affect a building as a whole is a lack of insulation, along with air and water infiltration from the building envelope. Improper insulation leads to inefficient operation of the mechanical systems associated with the building.”

Anatomy 101

First, a brief explanation of how these systems work to serve the building. The building envelope and waterproofing systems protect the building from external factors such as weather. Life safety provides adequate protection to the occupants in the event of a fire, power outage or other emergency. Life safety systems include, but are not limited to, fire pumps, sprinkler system, a fire alarm system, and stairwell pressurization fans.

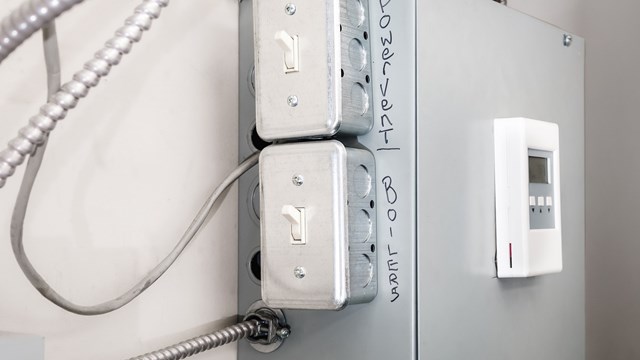

Electrical systems for smaller buildings consist of a simple power distribution system, which is transmitted through an electric meter (owned by the utility company) to panels, wiring and devices that are owned and operated by the building owner. Circuit breakers control the flow of power to the various circuits in the building. Convenience lighting requires a small load, while some appliances such as air conditioners require a heavier load.

Mechanical systems can be very simple for smaller buildings and more complex for high-rise buildings. Typically, smaller buildings consist of a central boiler for heat distribution of steam or hot water through baseboard heaters. Air conditioning is typically supplied by individual window or through-wall air-conditioning units. Larger, high-rise buildings consist of more complex systems, including combinations of a central boiler plant, rooftop air handling units, exhaust fans, fresh air intake, absorption chillers and/or cooling towers.

Plumbing systems for smaller buildings typically consist of one water main entering the building with domestic water distributed throughout the building branch piping. Water flow is dependent on street pressure. For larger buildings, the use of water-circulating pumps, or rooftop water towers, are used to ensure that the water pressure is adequate for all sections of the building.

William J. Pyznar, P.E., principal of The Falcon Group, which has offices in New Haven, Connecticut, says each piece of equipment associated with one of the main building systems has an anticipated useful service life.

“The useful service life is the duration, in years, in which the equipment is expected to properly operate,” he says. “The useful service lifetime varies by equipment and is typically included in the equipment schedule provided in a reserve study. There are numerous ways in which equipment can degrade and fail over time. Equipment that is properly maintained since installation should be able to last for the duration of the anticipated useful service life.”

Check Up Time

According to the experts, major building systems should be inspected every two to three years, and every building should have a maintenance plan that includes evaluations of all building systems to prevent large costly projects in the long run.

“Typically, the most efficient way to evaluate the performance of building systems is to conduct a building-wide physical survey and engineering evaluation,” Merritt says. “This evaluation includes the assessment of physical needs of site conditions and installations (sidewalks, parking areas and driveways), building envelope and appurtenances (roofing system and roof structures, existing waterproofing), building interior systems and finishes, and all primary building mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, and elevators systems.”

In the event of an immediate area of concern, it is highly recommended that building owners hire a registered design professional to inspect the integrity of all major building components and most important, ensure that the building is structurally sound.

Pyznar notes the frequency of routine service on a multifamily building’s central equipment will vary substantially, but excellent equipment performance begins with proper project commissioning to ensure proper installation and start-up

“After equipment is installed, maintenance should be performed by a qualified professional in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations,” he says. “The building manager and maintenance staff should have service contractors available for routine maintenance of central HVAC, plumbing, electrical, life safety, and elevator equipment.”

Jamey Ehrman, senior engineer for New York-based RAND Engineering & Architecture, DPC, says the Northeast’s unforgiving climate can be a major source of worry on a building’s operational systems.

“Water infiltration is the most common ailment of a building. It is typically caused by exposure to the elements,” he says. “The extreme hot summers, cold winters, UV exposure, and the daily temperature fluctuations during the winter that creates freeze/thaw cycles is literally punishing to the building fabric, and often the cause of water infiltration issues and unsafe façade conditions.”

Size Matters

The more building that a system needs to support, the more said system needs to exert. This may seem like common sense, but there are intricacies herein. Mechanical systems for smaller buildings require less maintenance due to the simplicity and size of the systems. For instance, a low-rise building heated by a steam boiler and gravity return-type system through cast-iron radiators can provide years of service with minimal maintenance, such as steam trap replacement and regular cleaning of the tubes within the steel tube. For larger high-rise buildings, the systems tend to be more complex, requiring additional components.

“As an example, a steam boiler system for a high-rise building would require condensate return pumps and tanks in addition to the boiler, traps, and radiators,” Merritt says. “Simply put, the additional components become an additional source of maintenance, and subsequently potential problems down the road.”

Pyznar adds that larger buildings typically have a larger maintenance budget that can more easily accommodate costly projects such as a cooling tower or boiler replacement. Smaller buildings need to carefully plan for future upgrades and replacements.

“It is highly recommended that all multifamily buildings, large and small, have their reserve funds routinely evaluated by a qualified reserve specialist,” he says.

Taking Charge

While—according to Mike Zimmerman, a principal engineer with Allied Consulting Engineering Services in Warwick, Rhode Island—there are very few code-mandated maintenance requirements for multifamily properties in New England, insurance companies are fairly vigilant about maintaining the safety and functionality of building systems, in the interest of protecting both life and property.

Zimmerman points out that code does mandate fire protection systems, and that code applies specifically to the process of building, and not buildings as they stand per se. That said, insurance companies require certificates of inspection for boilers over a certain size, and it's just sensible that buildings and all of their components should be maintained in a safe condition. “Ultimately, the liability rests upon the building owner,” Zimmerman explains.

“The building staff should familiarize itself with early indicators of problematic conditions,” Merritt says. “The staff, board, and managing agent can then coordinate a regular maintenance plan to ensure the proper inspections are performed, and any necessary repairs are specified and carried out by a qualified design professional.”

A multifamily building’s board or shareholders have a fiduciary responsibility to act in the best interest of the building, and typically make top-level decisions regarding building projects and maintenance practices.

“The management and facilities staff is responsible for carrying out projects and maintenance tasks on behalf of the board,” Pyznar says. “Every facilities staff has a different range of expertise and resources. Some buildings or communities have a large team of full-time maintenance staff members, allowing for the majority of daily and annual maintenance work to be performed in-house. Smaller buildings might have a part-time super who is responsible for daily maintenance items only.”

Since the members of a board are typically volunteers who are elected to their position, they need to delegate responsibilities so that the building can operate in a practical fashion. Having building maintenance personnel, building management, and even residents keeping an eye out for issues that need to be addressed is considered part of good practice.

“Quite often, analyzing these systems goes beyond the expertise of building maintenance personnel and building management—which is why building owners often retain the services of heating system service contractors, plumbers, electricians, elevator service companies, etc.,” Ehrman says. “For more complicated issues, it may be necessary to bring in an architect or engineering specialist for that specific issue. As far as specifics to a schedule, that is really dependent on the type of system within a building.”

Collaborate to Coexist

While, as Zimmerman previously stated, it falls to the owner in the end to ensure that a building is safe and secure, that owner is by no means acting alone. “Building owners should collaborate with management, building maintenance personnel, contractors and architectural/engineering professionals,” says Ehrman, as the depth of responsibility for maintaining a multifamily residence is much too great for one person, or even several qualified persons, to oversee on their own. It truly takes a village. And given the diversity of systems, from water to sewer to electrical to HVAC, all mandated by their own codes and with their own specific inspection time lines, it pays (read: saves time, heartache and money) to have all of the requisite maintenance information, requirements and scheduling readily available for a board to reference.

Keith Loria is a frequent contributor to New England Condominium. Staff writer Michael Odenthal contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment