Susan Jones wants to join the board of trustees. She’s been a unit owner for a few years and really believes that she can make a difference to the association. When it comes to co-op and condo boards, many members join because they have a personal issue that’s important to them and they want to see it through. Not Susan; she has no personal agendas, she’s an honest, hard-working woman. As a matter of fact, when the board decides to repair a few older roofs, Susan eagerly recommends her husband’s roofing company for the job.

On the other hand, John Davis can’t wait to start his term as a board member. He’s convinced that he’s the only one who can really see to it that his unit will be taken care of. He is also ready to make financial decisions that will benefit him in the long run.

It’s an unfortunate fact of condominium life: Board members’ responsibilities and their personal agendas intermingle more often than they should and, in both of these cases, the board members are pushing the envelope when it comes to conflict of interest.

Board members have a fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders, unit owners, and tenants living in their co-op or condo. This means, in simplest terms, that their loyalty cannot be divided. They cannot serve two masters. They must place the interests of their community above all other interests—including their own. In legal terms, conflict of interest “is a term used to describe the situation in which a public official or fiduciary who, contrary to their obligation and absolute duty to act for the benefit of the public or a designated individual, exploits the relationship for personal benefit—typically pecuniary.” And any member of a “condominium, cooperative or HOA board is a fiduciary.”

“Most, if not all, board members are volunteers, but that’s a lot of power in one place and it’s important to prevent it from being abused,” says Adam J. Cohen, a partner at the law firm of Pullman & Comley LLC in Bridgeport, Connecticut. “For example, board members shouldn’t be getting more maintenance than other unit owners. They are being given this responsibility, but it’s a trust. We call it ‘ordinary care,’ which is the care that a reasonable man would exercise under the circumstances.”

John Davis is definitely not exercising ordinary care. “People who get on the board to benefit themselves create a conflict of interest for the board,” says attorney Charles A. Perkins, Jr., a senior partner at the law firm of Perkins & Anctil in Westford, Massachusetts. “They think, ‘I want better landscaping in front of my unit,’ or ‘I want to lower the condo fee to sell my unit better.’ This is not what a board member ought to be. When you are on the board you have to hold yourself up to a higher standard.”

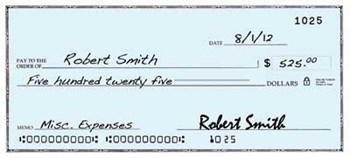

In Susan’s case, she may or may not realize that her friendly recommendation could be a financial conflict of interest to her board member duties. A financial conflict occurs when a contract is awarded to any family member—including an extended family member—or when the contract is awarded to a business that the board member has any interest in.

“Financial conflicts are often the easiest to discover and prevent, but can be the most costly if not discovered and prevented,” says Franklin Pilicy, attorney at the Law Office of Franklin G. Pilicy in Watertown, Connecticut.

However, conflict of interest—even a financial one—is not necessarily something that can’t be allowed. “If one of the board members, or their family members, is a contractor, they aren’t necessarily disqualified from doing work on the condo,” explains attorney Foster Cooperstein in Newton Centre, Massachusetts. “The board just has to get pricing elsewhere, too, and make sure that the board member is the most qualified and best-priced.”

Another example of a conflict of interest is when a board is establishing priorities for capital improvements and board member occupied/owned buildings receive priority. “Repair conflict is absolutely wrong and is a terrible thing to do,” says Cooperstein. “If someone was doing contractor work for the condo and an extremely minor thing was done for a trustee—even if it only took a few minutes—it’s absolutely wrong to do.”

Checks and Balances

The best checks and balances against any conflicts start with the board of directors or the trustees, who should always be alert to such potential issues. “There are many provisions of the condominium statutes and documents that provide checks and balances on the exercise of powers by the board of directors,” says Pilicy. “Each association is governed by state law and the association’s documents. Certainly there are differences from state to state between condominium laws and an association has the right to establish policies regarding conflicts of interests. However, it is rare for an association to have such policies.”

The easiest way to avoid most conflicts is to remember that any benefit that is not available to all unit owners should be avoided. “Disclosure to the entire association is the best protection against directors receiving such perks,” says Pilicy.

If a unit owner uncovers a conflict, it’s important to report it to the board as soon as possible. “If the unit owner feels the matter is being ignored, they could forward a written protest to the association’s attorney,” says Pilicy. “The association’s documents likely protect the unit owner’s right to speak at a board meeting or unit owner meeting. The documents may also allow the unit owner(s) to petition the board for a meeting to remove any or all board members. Each conflict situation should then be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.”

Cooperstein explains that if a significant amount of money is involved, the unit owner could have the board bring action. “There’s no absolute line between impropriety and real corruption. Real corruption is, ‘Here you do the work, we don’t care what it costs, we haven’t priced it, and we don’t know if you can do the work.”

When it comes to conflicts of interest, board members aren’t the only one who have to toe the line. “When a board hires a manager, they are delegating a part of their duties and they monitor what that person is doing in accordance to their contract,” says Cohen. “There are red flags to watch for, including not corresponding in a timely way, not producing copies of records regularly or on demand, complaints from the unit owners and money appears to be missing.”

A potential management conflict may also occur when a management company provides maintenance services too. “The best approach to safeguard against such conflicts is for the board to review management contracts at least annually and to interview all vendors for major contracts,” says Pilicy. “It’s recommended that boards interview two or three vendors for any major service and that a board officer sign each contract.”

Know the Rules

So how do you prevent board members like John from doing things their own way? First, know the rules. Every board member must follow its own rules, especially those spelled out under any state Condominium Act which outlines the laws that govern all community associations in the state. All boards are legally required to follow the procedures set forth in these pieces of legislation. If any board member is unfamiliar or unsure of how to interpret the law, and/or specific rules and regulations, they should consult with their association’s attorney.

The other main documents that govern co-op and condo living include the certificate of incorporation—and the proprietary lease in the case of co-ops—and the declaration of covenants, conditions and restrictions or CC&Rs for condos, as well as the bylaws and house rules and regulations that govern day-to-day activities in both. If an issue arises that isn’t covered in these documents, it doesn’t mean that the board as a whole, or an individual board member, can simply do what he or she chooses. One of the keys is board interaction with individual unit owners.

Second, board members must keep their feelings out of their responsibilities and almost everyone who has ever served on a board agrees that working with an attorney is paramount in ensuring that the board follows the letter of the law and protects itself from liability and fiduciary responsibility. A board member who consistently tries to break or selectively “forgets” about the rules, should not serve or be re-elected. Keeping a loose cannon like this on the board can lead to all kinds of problems—particularly if their behavior is known and acknowledged. Acting in bad faith, or allowing bad faith to persist can have serious legal ramifications, including paying damages out-of-pocket in the event of a lawsuit or criminal investigation.

If a board member makes an unintentional mistake when it comes to conflict of interest, it’s never too late to start over. It’s so vital to follow the rules, step out when there’s a conflict of interest and remember that today's decisions are tomorrow's precedents.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to New England Condominium.

Leave a Comment